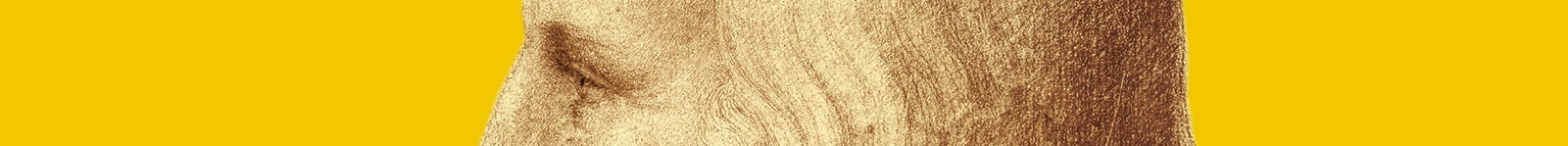

ATTRIBUTED TO FRANCESCO MELZI (1493-1570)

A portrait of Leonardo

c.1515-18RCIN 912726

A portrait drawing of the head of Leonardo da Vinci, turned in profile to the left; with long wavy hair and a flowing beard. Inscribed below: LEONARDO / VINCI.

This is the only reliable surviving portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). It was most probably executed towards the end of his life by his pupil Francesco Melzi, perhaps with enlivening strokes by Leonardo himself in the lower part of the hair. The sheet has been shaped for mounting and shows signs of having been attached to a support, lifted and restored at an early date; the paper has discoloured from long exposure to light. This was presumably therefore the portrait seen by Giorgio Vasari in Melzi’s villa, as recorded in his Lives (RCIN 1152359–61) in the context of the thousands of drawings by Leonardo that Melzi inherited, more than five hundred of which entered the Royal Collection in the seventeenth century: ‘he holds them dear, and keeps such papers together as if they were relics, in company with the portraits of Leonardo of happy memory’(Vasari 1996, I, p. 634).

Early writers were agreed that Leonardo was beautiful (even if none had known him personally), and that this was a natural, God-given corollary of his personal qualities and his abilities as an artist. But of those early texts, only the appendix to the brief biography by the so-called Anonimo Gaddiano gives some detail of Leonardo’s appearance, describing him as having ‘a beautiful head of hair down to the middle of his breast, in ringlets and well arranged’ (E.g. Goldscheider 1959, p. 32.). There is no evidence that Leonardo was bearded until his last years: before the sixteenth century a beard would have been seen as odd on an Italian – they were the preserve of the barbarous, Germans, Orientals, figures from ancient history and biblical times, philosophers, hermits and penitents.

It was probably through Vasari’s acquaintance with this drawing in Villa Melzi that the profile frontispiece to the biography of Leonardo in his Lives took the form that it did, with the addition of a cap; and from Vasari’s illustration stemmed posterity’s image of Leonardo. Intriguingly, the standard type of the Greek philosopher Aristotle converged with this likeness of Leonardo during the sixteenth century, to become the accepted pattern for the venerable natural philosopher. This fitted so perfectly the perception of Leonardo’s character that the now-famous drawing of an old man with furrowed brow, long beard and distant gaze in Turin (Biblioteca Reale) was unquestioningly accepted as a self-portrait of Leonardo when it surfaced in the early nineteenth century. That drawing passed into common currency as his definitive likeness and will doubtless retain that status. Only recently has it been pointed out that the Turin drawing – if it is by Leonardo at all – must on grounds of style be a work of the 1490s, when he was in his mid-forties, and thus cannot possibly be a self-portrait.

Text adapted from Portrait of the Artist, London, 2016

This is the only reliable surviving portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). It was most probably executed towards the end of his life by his pupil Francesco Melzi, perhaps with enlivening strokes by Leonardo himself in the lower part of the hair. The sheet has been shaped for mounting and shows signs of having been attached to a support, lifted and restored at an early date; the paper has discoloured from long exposure to light. This was presumably therefore the portrait seen by Giorgio Vasari in Melzi’s villa, as recorded in his Lives (RCIN 1152359–61) in the context of the thousands of drawings by Leonardo that Melzi inherited, more than five hundred of which entered the Royal Collection in the seventeenth century: ‘he holds them dear, and keeps such papers together as if they were relics, in company with the portraits of Leonardo of happy memory’(Vasari 1996, I, p. 634).

Early writers were agreed that Leonardo was beautiful (even if none had known him personally), and that this was a natural, God-given corollary of his personal qualities and his abilities as an artist. But of those early texts, only the appendix to the brief biography by the so-called Anonimo Gaddiano gives some detail of Leonardo’s appearance, describing him as having ‘a beautiful head of hair down to the middle of his breast, in ringlets and well arranged’ (E.g. Goldscheider 1959, p. 32.). There is no evidence that Leonardo was bearded until his last years: before the sixteenth century a beard would have been seen as odd on an Italian – they were the preserve of the barbarous, Germans, Orientals, figures from ancient history and biblical times, philosophers, hermits and penitents.

It was probably through Vasari’s acquaintance with this drawing in Villa Melzi that the profile frontispiece to the biography of Leonardo in his Lives took the form that it did, with the addition of a cap; and from Vasari’s illustration stemmed posterity’s image of Leonardo. Intriguingly, the standard type of the Greek philosopher Aristotle converged with this likeness of Leonardo during the sixteenth century, to become the accepted pattern for the venerable natural philosopher. This fitted so perfectly the perception of Leonardo’s character that the now-famous drawing of an old man with furrowed brow, long beard and distant gaze in Turin (Biblioteca Reale) was unquestioningly accepted as a self-portrait of Leonardo when it surfaced in the early nineteenth century. That drawing passed into common currency as his definitive likeness and will doubtless retain that status. Only recently has it been pointed out that the Turin drawing – if it is by Leonardo at all – must on grounds of style be a work of the 1490s, when he was in his mid-forties, and thus cannot possibly be a self-portrait.

Text adapted from Portrait of the Artist, London, 2016