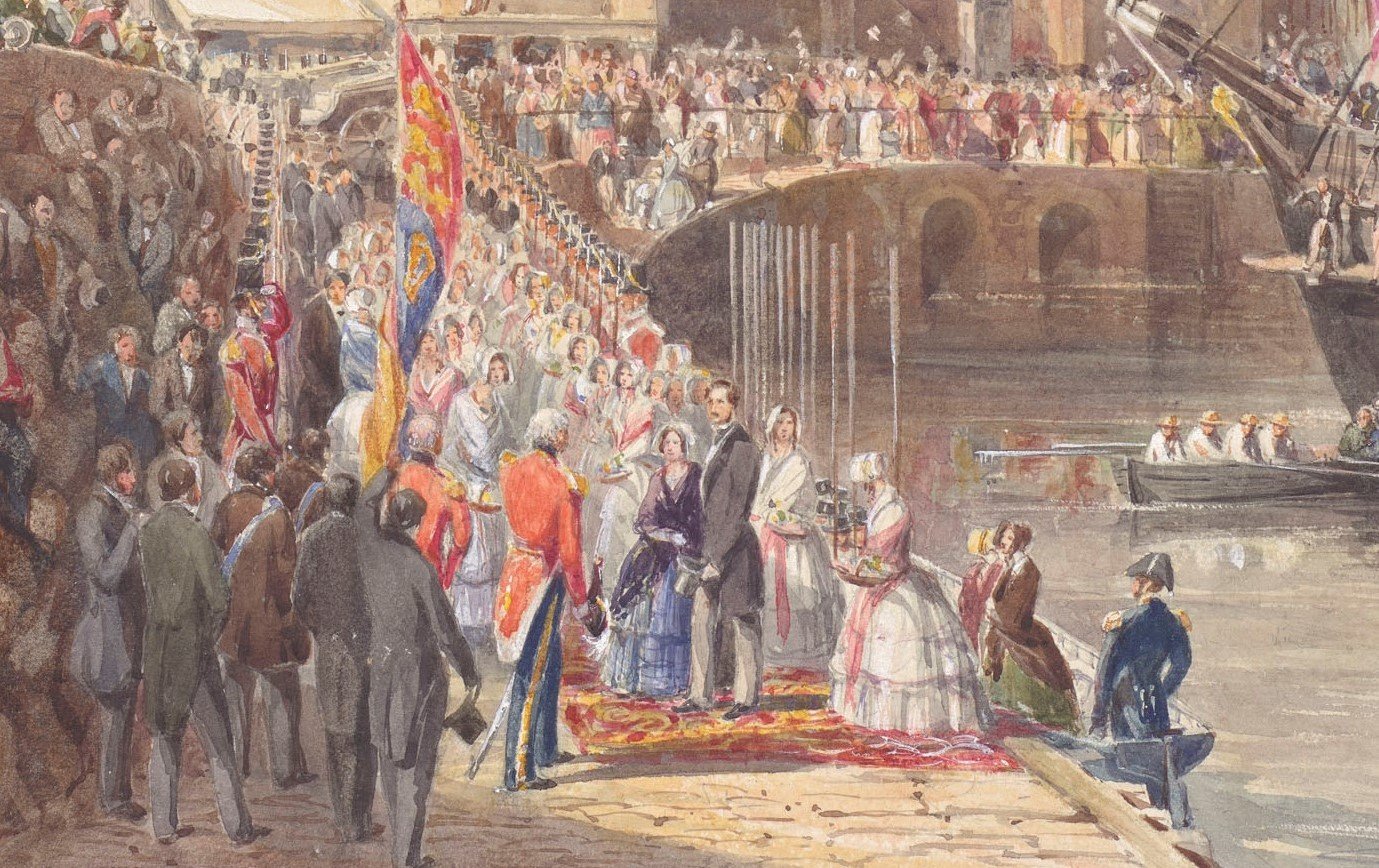

LOUIS HAGHE (1806-85)

The Great Exhibition: Moving machinery

c. 1851-2Pencil, pen and ink, watercolour, with touches of bodycolour and gum arabic | 29.5 x 54.5 cm (sheet of paper) | RCIN 919979

A watercolour view of display of moving machinery and engines at the Great Exhibition of 1851. With an arched top.

In his capacity as President of the Society of Arts, Prince Albert set up a committee to organise exhibitions with the aim of improving British industrial design. An exhibition in Birmingham in 1849 was followed by the first truly international exhibition, the Great Exhibition of Products of Industry of All Nations, held in Joseph Paxton's 'Crystal Palace' in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. Half the exhibition space was devoted to British manufacturing, and the other half was offered to foreign countries to display their achievements and specialisms. Six million people visited the exhibition to see over 100,000 exhibits from around the world, divided broadly into raw materials, machinery, manufactures and the fine arts; Queen Victoria herself visited no fewer than thirty-four times. The substantial profits were used to establish the South Kensington Museum, renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899. The Queen wrote to her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, that the inaugeration of the Great Exhibition was the "greatest day in our history."

Prince Albert commissioned fifty watercolours of the Great Exhibition, to be reproduced by Dickinson Bros in chromolithography, a new mechanical colour-printing process in keeping with the aims of the exhibition itself. Forty-four of the watercolours were executed by Joseph Nash (1808-78), and six by the Belgian artist Louis Haghe. Having moved to London at the age of seventeen, Haghe worked with the pioneering commercial lithographer William Day, spending eight years producing the chromolithographs for David Roberts's Sketches in the Holy Land (published 1842-9); he was a founder member of the New Watercolour Society in 1832 and left Day & Son in 1851 to become a full-time watercolourist.

The lettering of the lithograph points out that such machines could be used by untrained men to do work which formerly had to be carried out by skilled workmen at high wages. Visitors' feelings about the consequences of such industrialisation must have been heightened by the proximity of the machinery court to the medieval court, both in the western nave of the Crystal Palace, and the contrast between the new industrial machinery and the specimens of medieval and Gothic-revival art assembled by AWN Pugin.

Text adapted from Victoria & Albert: Art & Love, London, 2010

In his capacity as President of the Society of Arts, Prince Albert set up a committee to organise exhibitions with the aim of improving British industrial design. An exhibition in Birmingham in 1849 was followed by the first truly international exhibition, the Great Exhibition of Products of Industry of All Nations, held in Joseph Paxton's 'Crystal Palace' in Hyde Park, London, in the summer of 1851. Half the exhibition space was devoted to British manufacturing, and the other half was offered to foreign countries to display their achievements and specialisms. Six million people visited the exhibition to see over 100,000 exhibits from around the world, divided broadly into raw materials, machinery, manufactures and the fine arts; Queen Victoria herself visited no fewer than thirty-four times. The substantial profits were used to establish the South Kensington Museum, renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899. The Queen wrote to her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, that the inaugeration of the Great Exhibition was the "greatest day in our history."

Prince Albert commissioned fifty watercolours of the Great Exhibition, to be reproduced by Dickinson Bros in chromolithography, a new mechanical colour-printing process in keeping with the aims of the exhibition itself. Forty-four of the watercolours were executed by Joseph Nash (1808-78), and six by the Belgian artist Louis Haghe. Having moved to London at the age of seventeen, Haghe worked with the pioneering commercial lithographer William Day, spending eight years producing the chromolithographs for David Roberts's Sketches in the Holy Land (published 1842-9); he was a founder member of the New Watercolour Society in 1832 and left Day & Son in 1851 to become a full-time watercolourist.

The lettering of the lithograph points out that such machines could be used by untrained men to do work which formerly had to be carried out by skilled workmen at high wages. Visitors' feelings about the consequences of such industrialisation must have been heightened by the proximity of the machinery court to the medieval court, both in the western nave of the Crystal Palace, and the contrast between the new industrial machinery and the specimens of medieval and Gothic-revival art assembled by AWN Pugin.

Text adapted from Victoria & Albert: Art & Love, London, 2010