10 Greatest Treasures of the Royal Library

The Royal Library is a collection of some 240,000 books, manuscripts, coins and medals, spread throughout the royal residences, but with a core collection at Windsor Castle.

The Library was established in the 1830s during the reign of William IV after previous royal libraries had been given to the British Museum in the 18th and 19th centuries. Royal librarians built up the new library using existing royal book collections that had not been part of the transfers to the British Museum, and through purchases and gifts.

The earliest text in the Royal Library dates to c. 300 BC: an Egyptian funerary text on papyrus.

As the Library continues to acquire new holdings, including official gifts to The King, its collection spans across the ancient world to the present day. There are countless treasures, many of which have strong links to royal figures and history, but the ten listed here are considered by many to be amongst the most important books in the world.

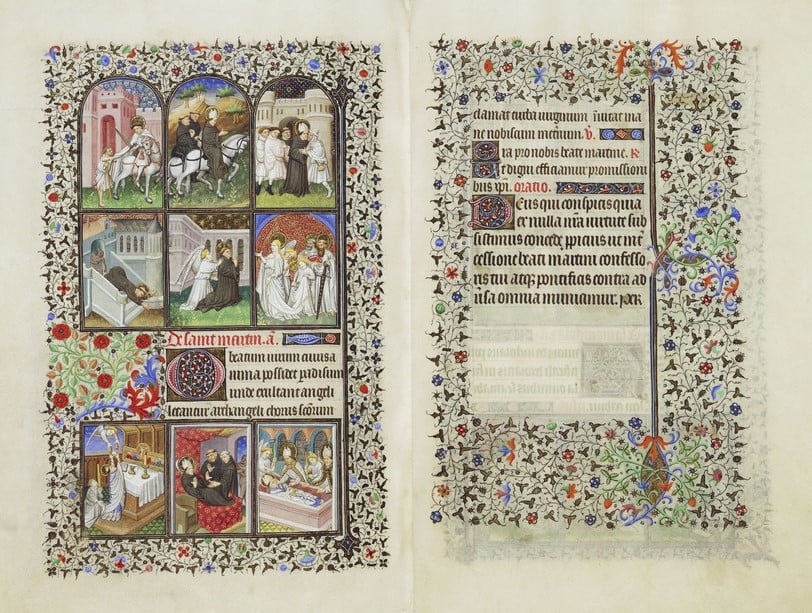

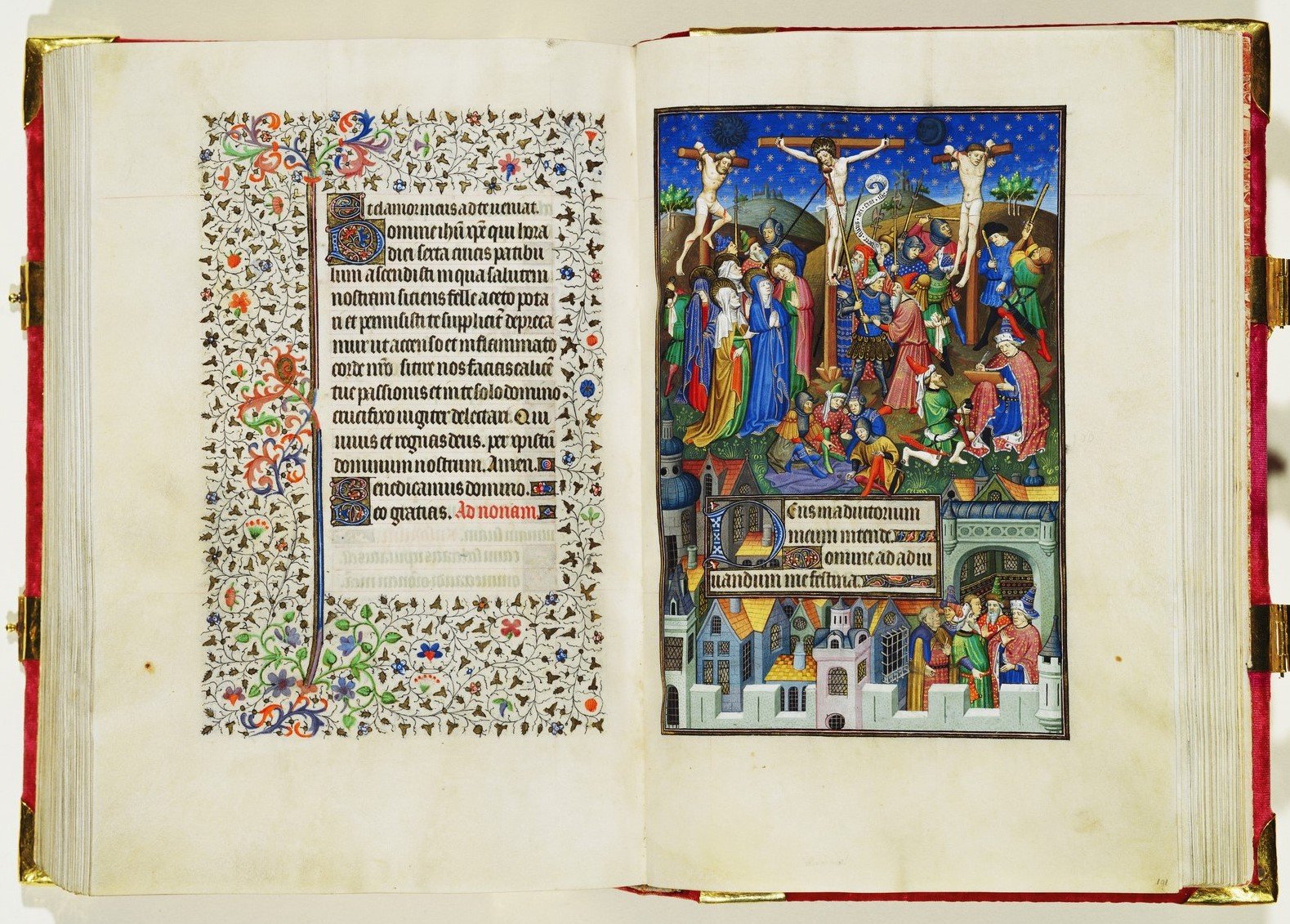

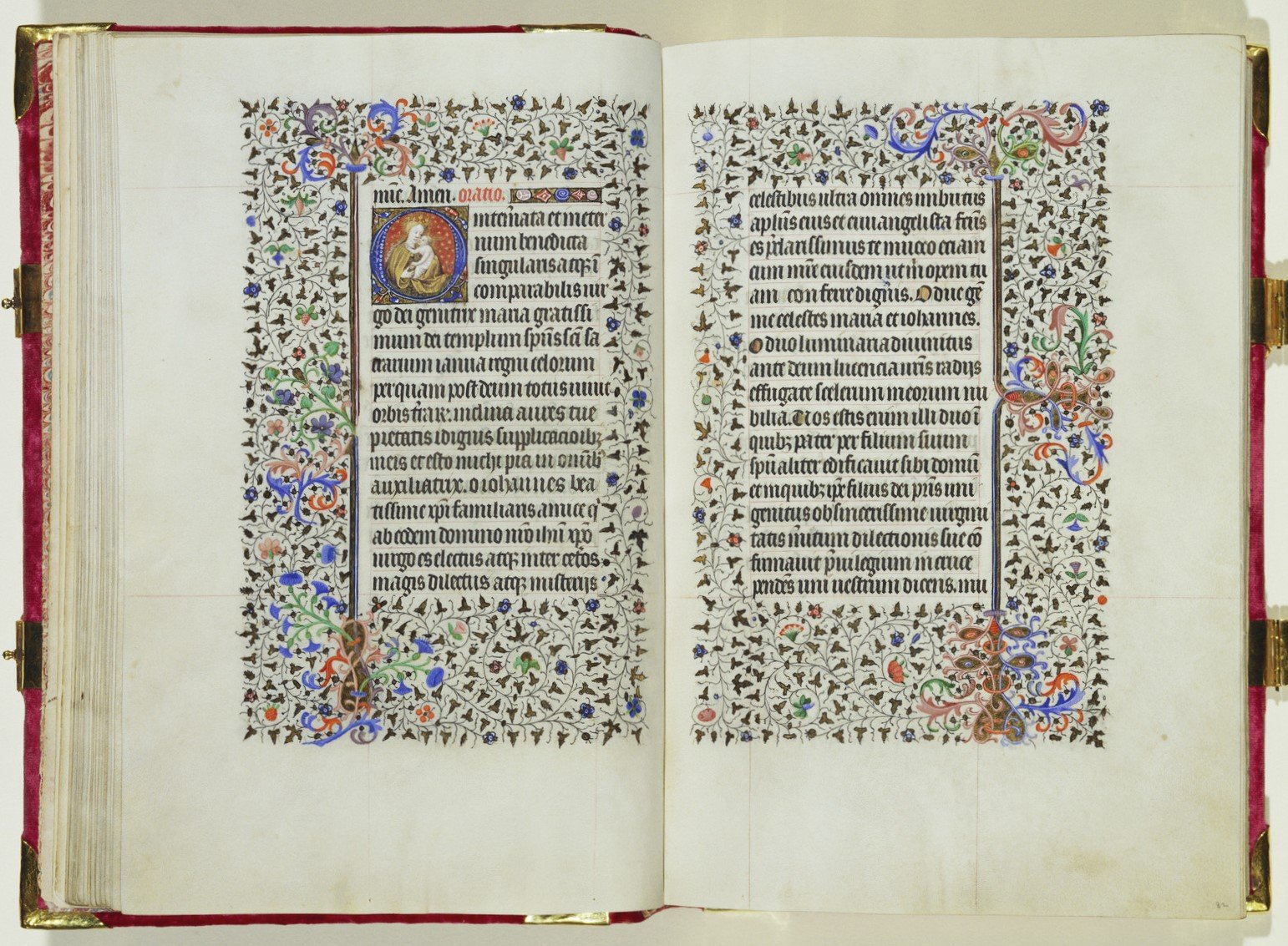

The Sobieski Hours

A book of hours contains prayers and devotional texts and is often dubbed ‘the bestseller of the Middle Ages’. It was a cornerstone of the European book trade, not only favoured as the standard prayer book of the time, but as a wedding gift and ABC for children.

The Sobieski Hours is named after its 17th-century owner, John III Sobieski, who added his initials to the cover. It is one of the finest illuminated manuscripts created in 15th-century Paris, displaying a portable gallery with hundreds of hand-painted images produced by three leading artists: the Master of the Bedford Hours, the Master of Sir John Fastolf, and the Master of the Munich Golden Legend. Their images bring to life historic personalities, biblical stories, charming medieval interiors, and sweeping landscapes with fairytale castles. This manuscript entered the Royal Collection in 1814 after it was bequeathed by Henry Benedict, Cardinal York to the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. When the Royal Library was established in the 1830s by King William IV, it became one of its greatest treasures.

Read more about The Sobieski Hours in our Collection Online.

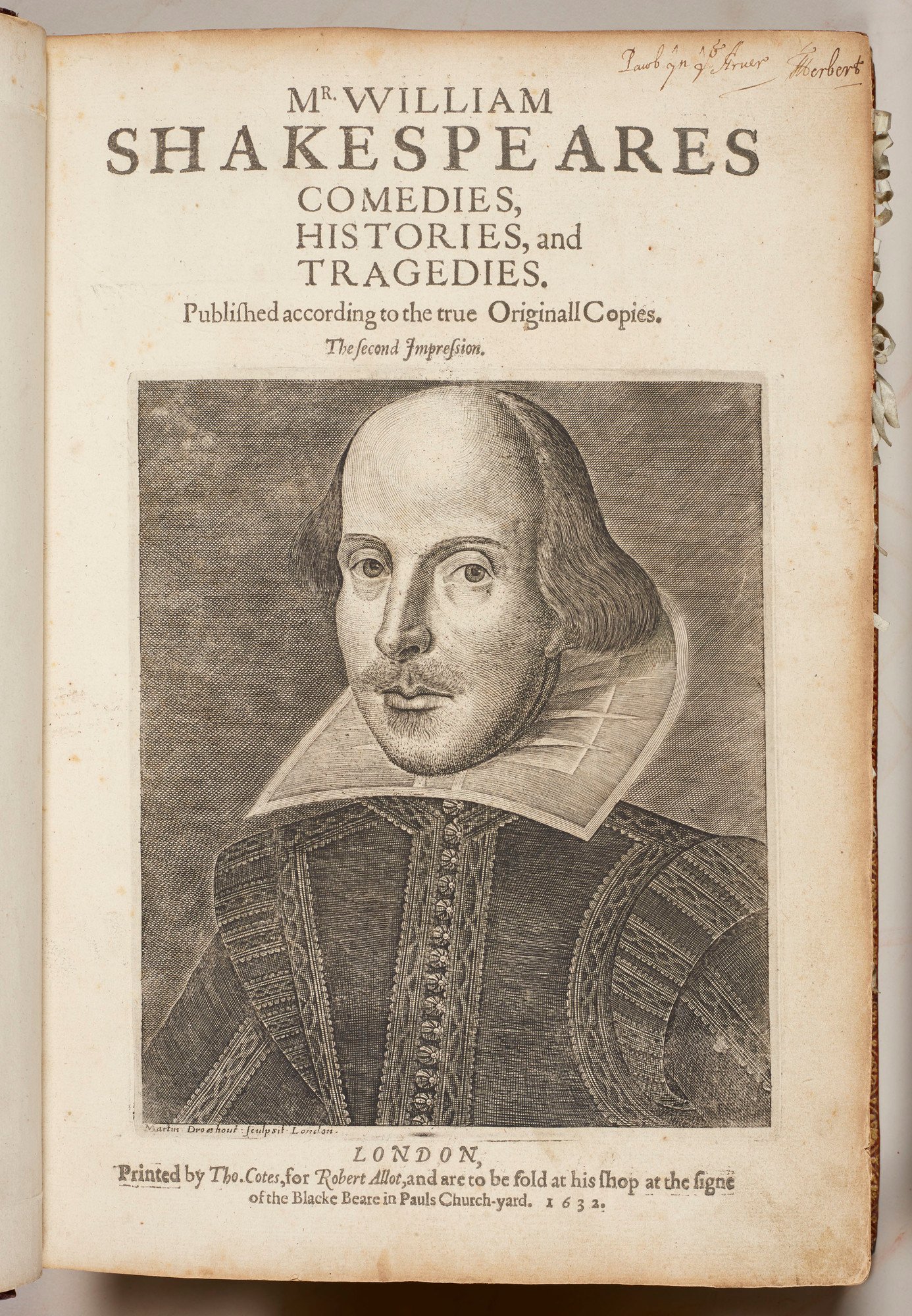

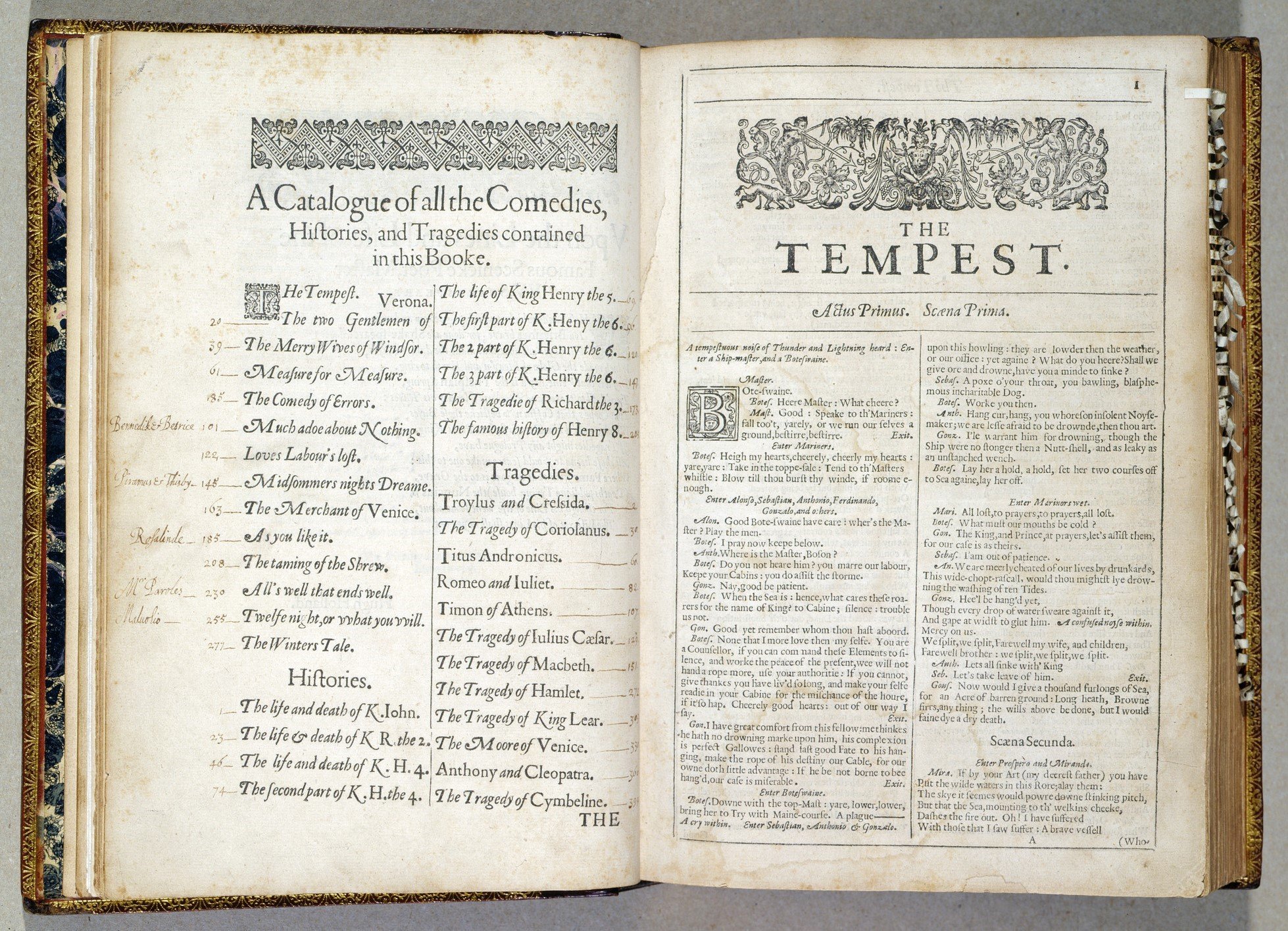

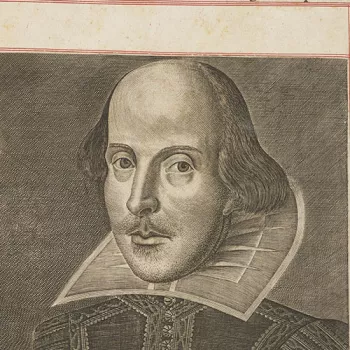

Shakespeare's Second Folio

The Second Folio, published in 1632, is the second edition of William Shakespeare’s collected plays. It was produced nine years after the First Folio, which gathered Shakespeare’s plays into a single volume for the first time.

The copy in the Royal Library was owned by Charles I, who read it while imprisoned at Windsor Castle during the Civil Wars. Inside, he wrote ‘Dum Spiro Spero’, Latin for ‘while I breathe, I hope’, a poignant phrase which appears in many of the books that were in his possession at this time. After Charles was executed, the book came to be owned by a series of collectors until it was purchased by George III in 1800, who also annotated it.

The Eikon Basilike

The Eikon Basilike, meaning ‘royal portrait’, is a memoir attributed to Charles I in which he justifies his actions during the English Civil Wars. Published a few days after the king’s execution in 1649, it was particularly influential in spreading the image of Charles the Martyr - the just, peace-loving and pious king who was martyred for his faith.

This copy may have belonged to Princess Sophia of the Palatinate, the youngest daughter of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I and VI. Inside, there is a print of Charles II after a portrait painting of the new king by Jan van der Hoecke. Charles may have given the print to the young princess during their unsuccessful courtship around 1649-50. The print has been cut down to fit in this copy, and on the back, ‘for the princess Sophia’ is written in Charles II’s handwriting. Sophia later married Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover, and in 1701 was named the heir to the British throne.

Read more about the Eikon Basilike in our Collection Online.

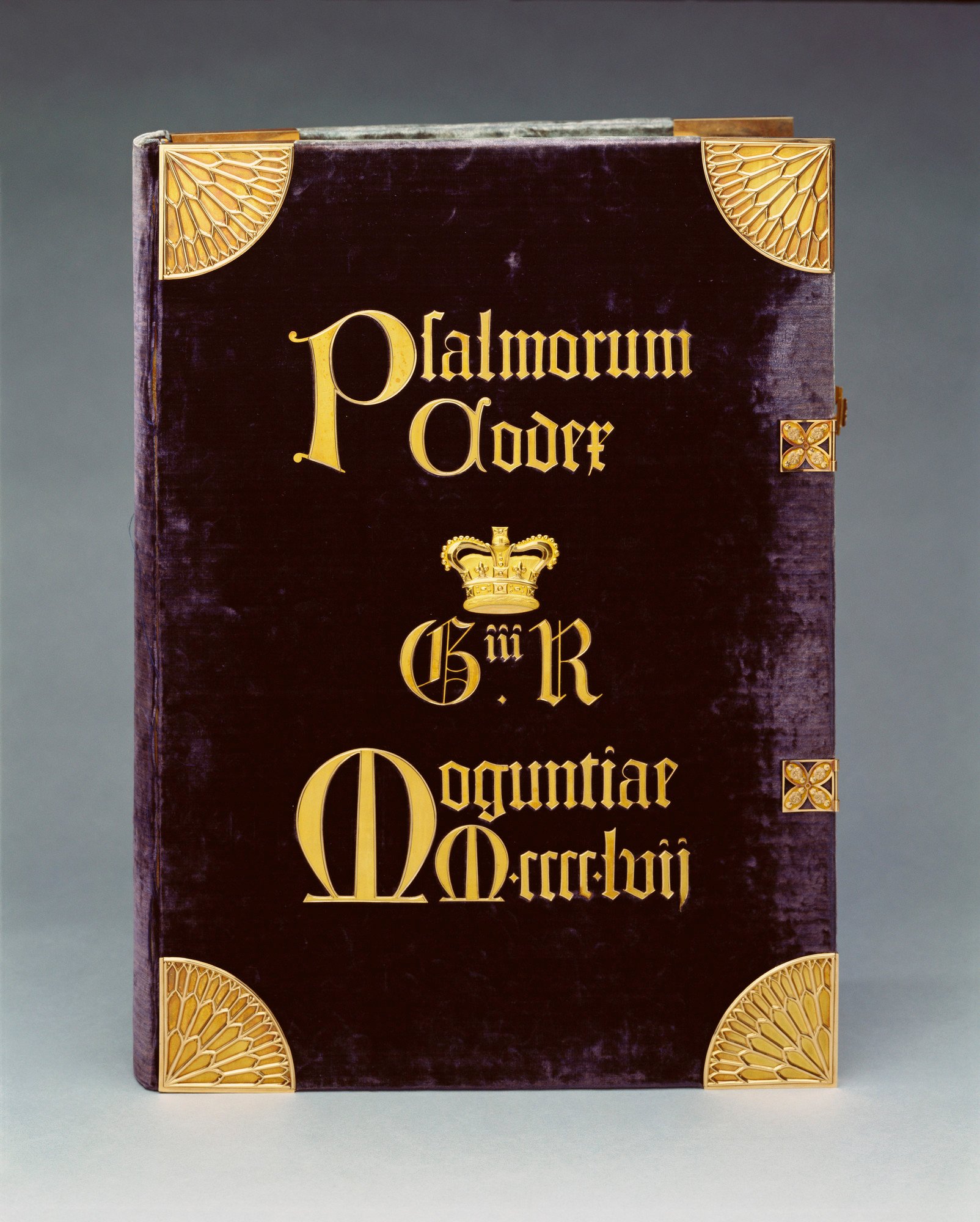

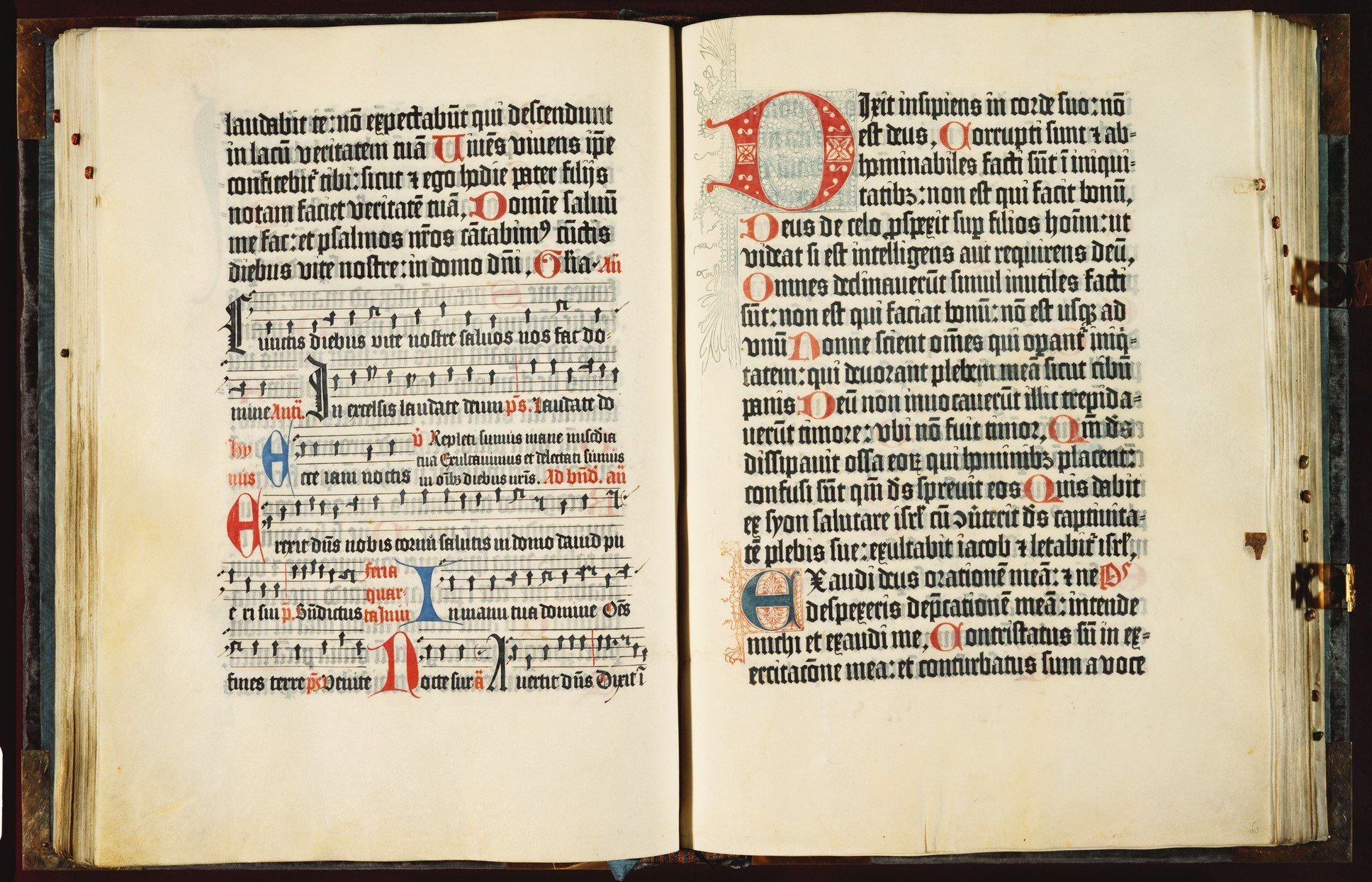

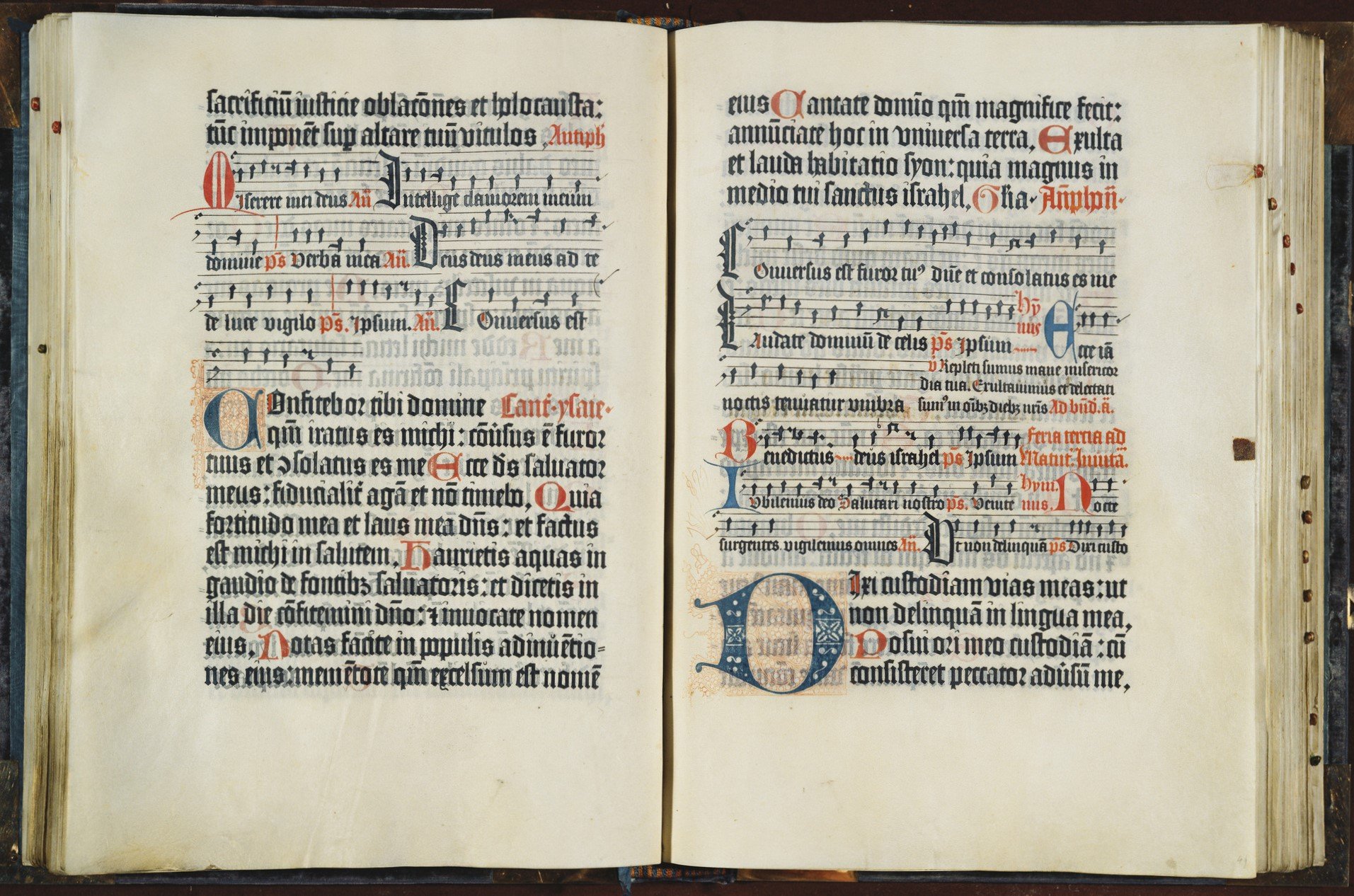

The Mainz Psalter

The Mainz Psalter is a collection of biblical psalms, first printed in 1457. It is the second title to be printed with movable metal type, the first being the Gutenberg Bible printed in Mainz (present-day Germany) around 1453-5.

The Psalter was printed in two lengths. It is rare, with only ten copies surviving. Four of these are a longer issue made specifically for the diocese of Mainz. The remaining six, which includes the Royal Library’s copy, are shorter versions made for general use. The Psalter is the first known book to have been printed in red and black ink. To do this, metal characters were individually removed from the printing press’s frame, inked red, and then reinserted amongst the rest of the letters inked black before pressing. This process, although time-consuming, meant that the colours did not overlap.

Before the invention of printing, every book had to be painstakingly written out by hand. It was a meticulous and expensive process carried out by specially trained scribes which could take months – sometimes years – to complete. Printing books mechanically brought about a revolution in reading and education.

The Mainz Psalter is the earliest printed book in the Royal Library. Learn more about the Mainz Psalter in our Collection Online.

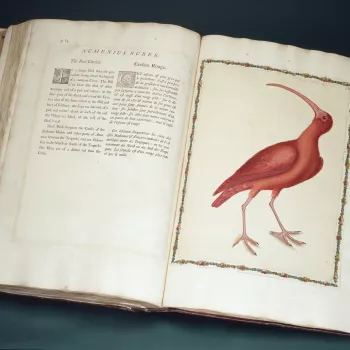

The Birds of America

John James Audubon, the self-taught artist, naturalist, and ornithologist, dedicated his life to the study of birds. His immense publication, Birds of America, contains 435 hand-coloured printed illustrations made from his original paintings, which depict life-size birds in their natural habitat. It was published between 1827 and 1838 and is one of the best-known natural history books to have ever been created. Audubon’s illustrations were innovative. Until the invention of prism binoculars in the mid-19th century, ornithologists would use ‘study skins’ – a bird that had been shot, stuffed and positioned on its back with its wings folded and beak extended. This ensured that the specimens would fit tidily in a drawer. Instead, Audubon would use wires and pins to arrange the birds into life-like positions, either hunting, preening, perched or in flight.

The Birds of America was printed in ‘double-elephant’ folio, which takes its name from the size of the paper (approximately 100 x 67 cm). It is a monumental book. The copy in the Royal Library is one of 120 ‘double-elephant’ editions to survive in their entirety.

Read more about the conservation of Audubon’s Birds of America.

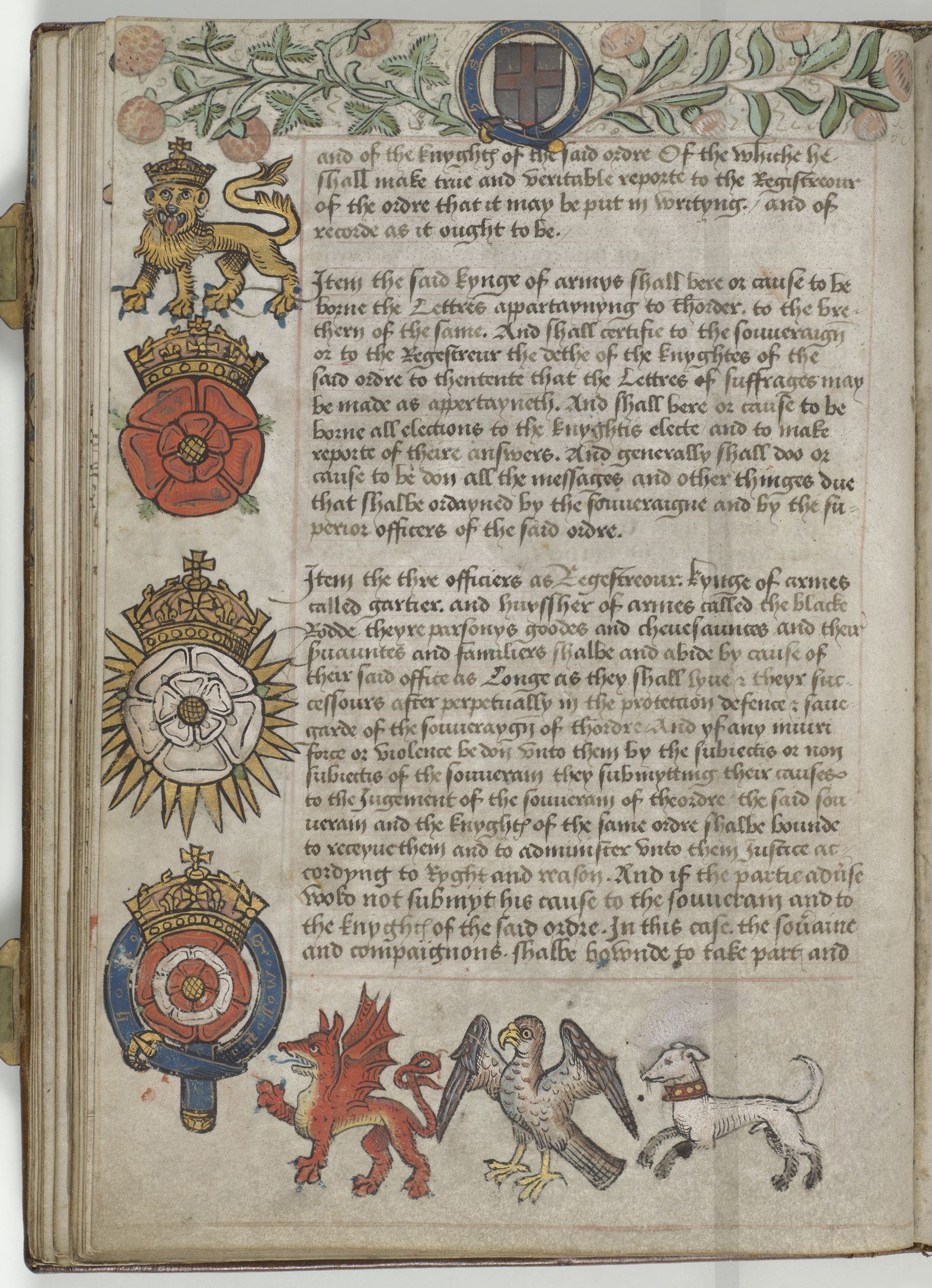

The Wriothesley Garter book

The Wriothesley Garter book is a beautifully illustrated manuscript that contains a variety of records on heraldic matters, especially for the Order of the Garter, and heralds’ fees and oaths. It was compiled by Sir Thomas Wriothesley, who occupied the post of Garter King of Arms from 1505 to 1534. He is depicted here, in what is believed to be the first contemporary view of the opening of parliament at Blackfriars in 1523. Henry VIII is enthroned in the middle, while Wriothesley himself can be seen on the king’s left wearing the distinctive tabard of a herald, alongside officers of the Royal Household.

Read more about The Wriothesley Garter book in our Collection Online.

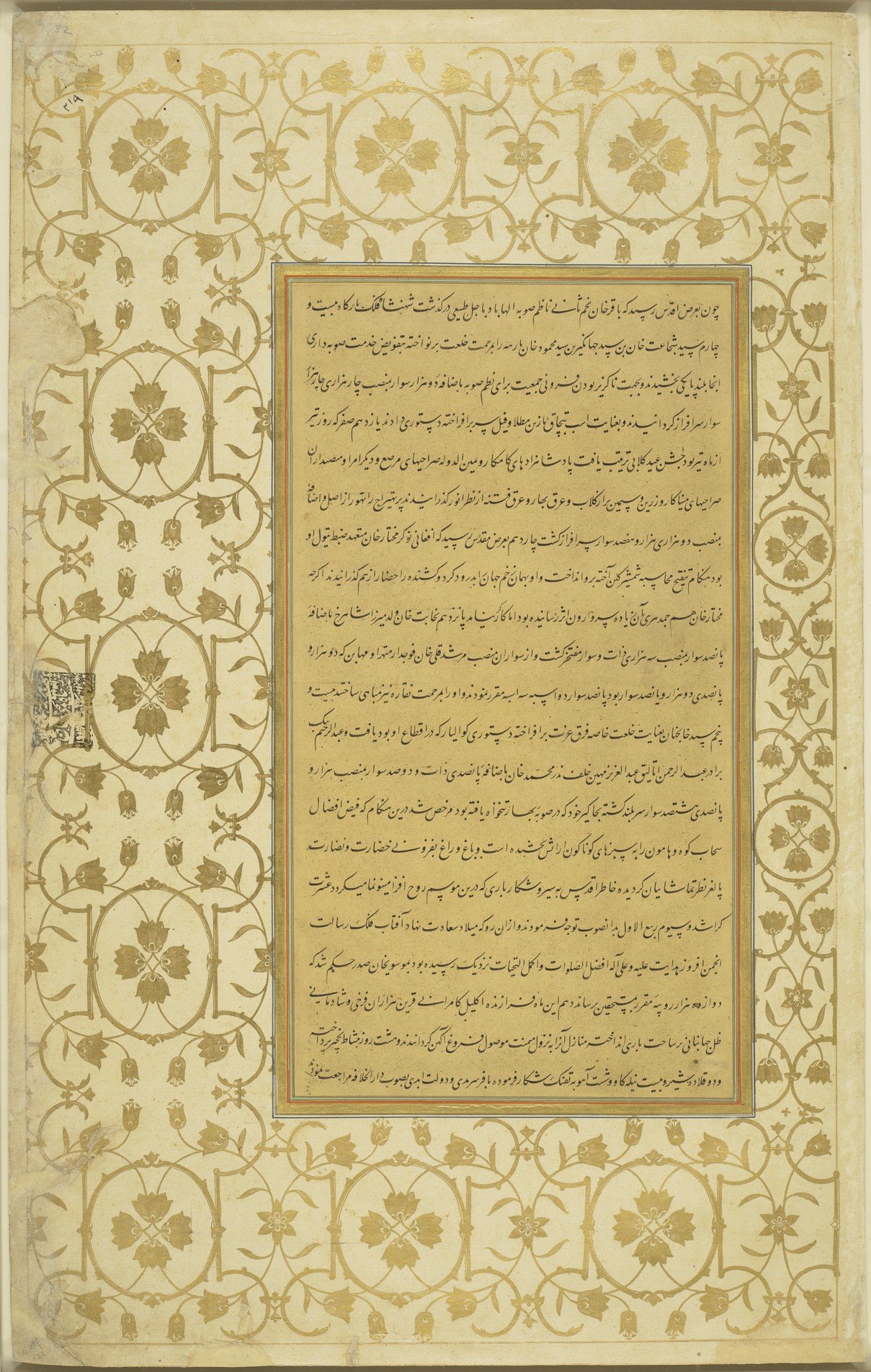

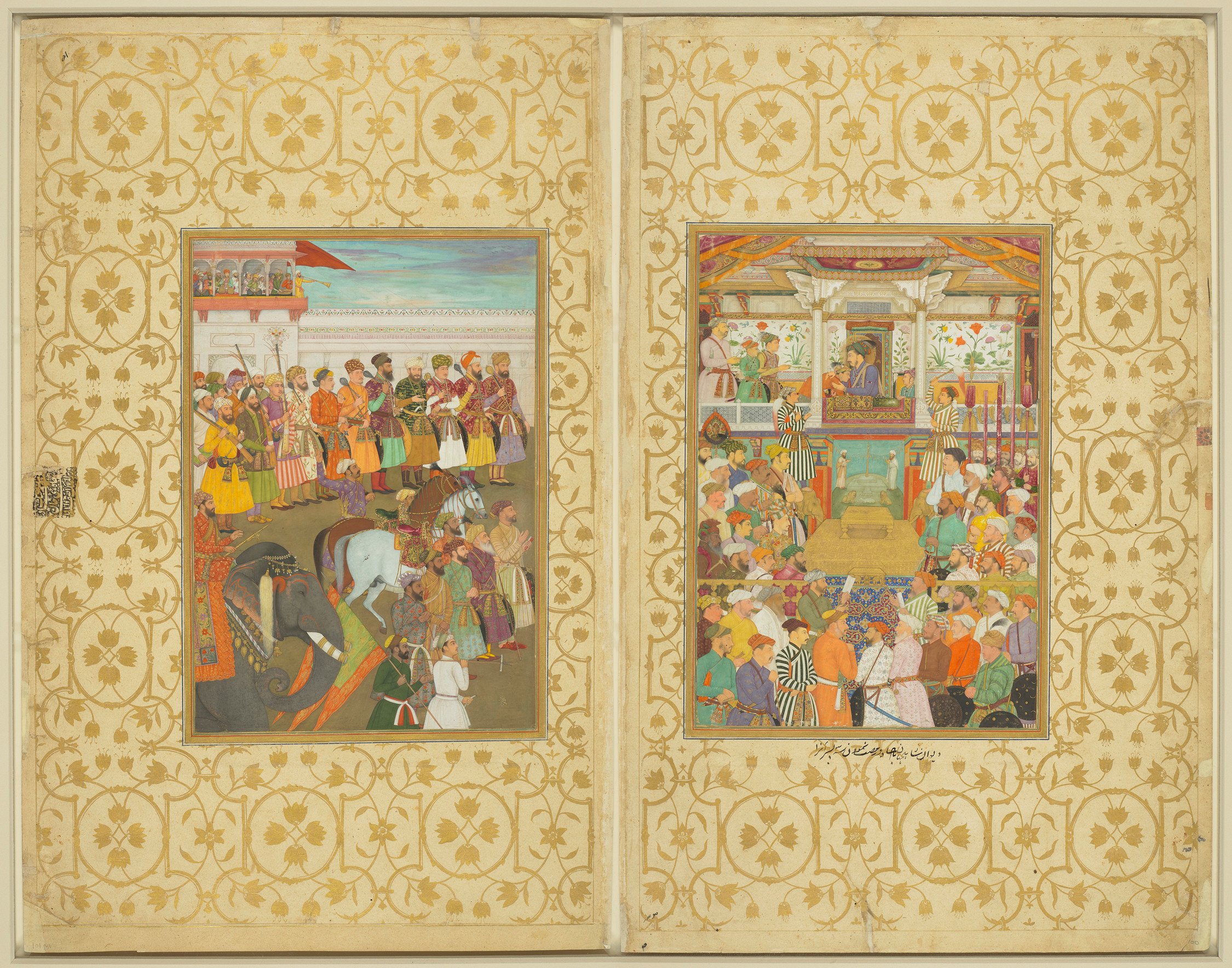

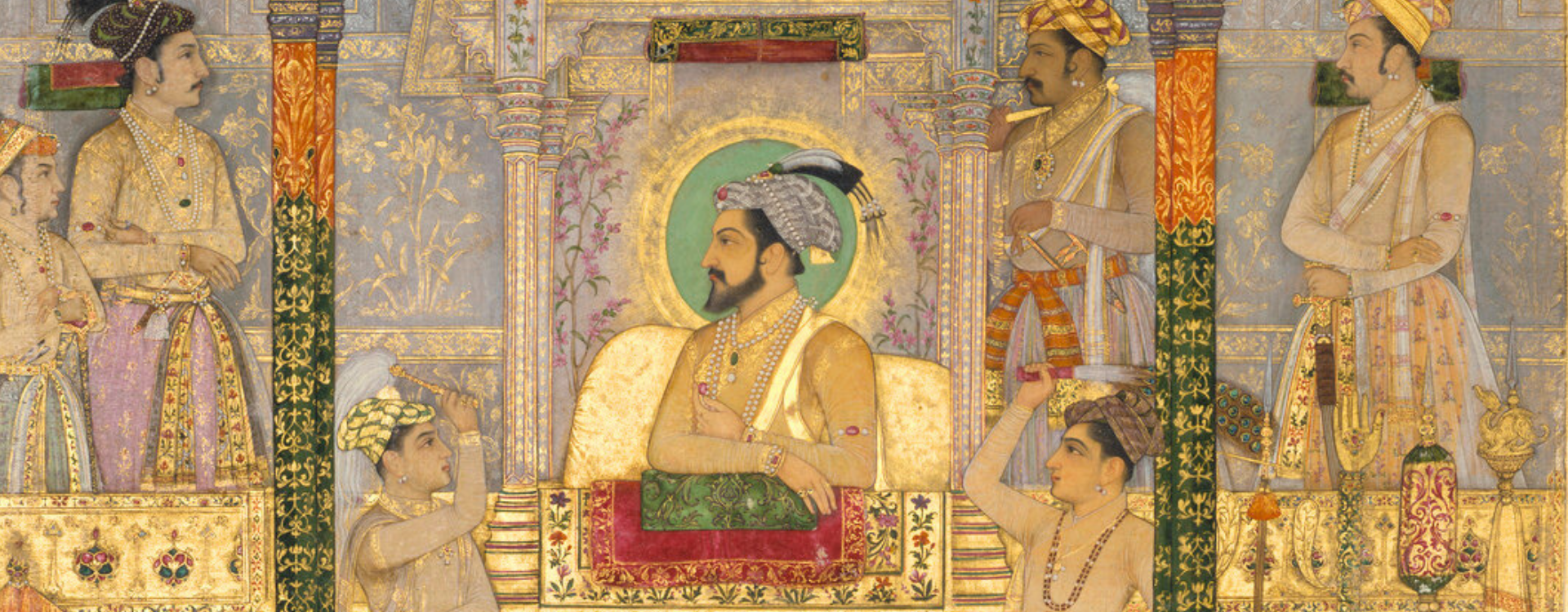

Padshahnamah (The Book of Emperors)

The Padshahnamah was commissioned in the 17th century by Shah-Jahan, the fifth Mughal emperor, as a piece of propaganda to celebrate his reign and dynasty. The Mughal Empire ruled over most of modern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The manuscript in the Royal Library is unique: the only contemporary illustrated volume of the Padshahnamah to survive. It contains some of the finest Mughal paintings ever made, which depict events in the emperor’s life such as magnificent durbars (a public reception), lavish processions and glorious victories on the battlefield.

The Padshahnamah was a gift from Saadat Ali Khan, Nawab of Awadh (in northern India), to George III in 1799.

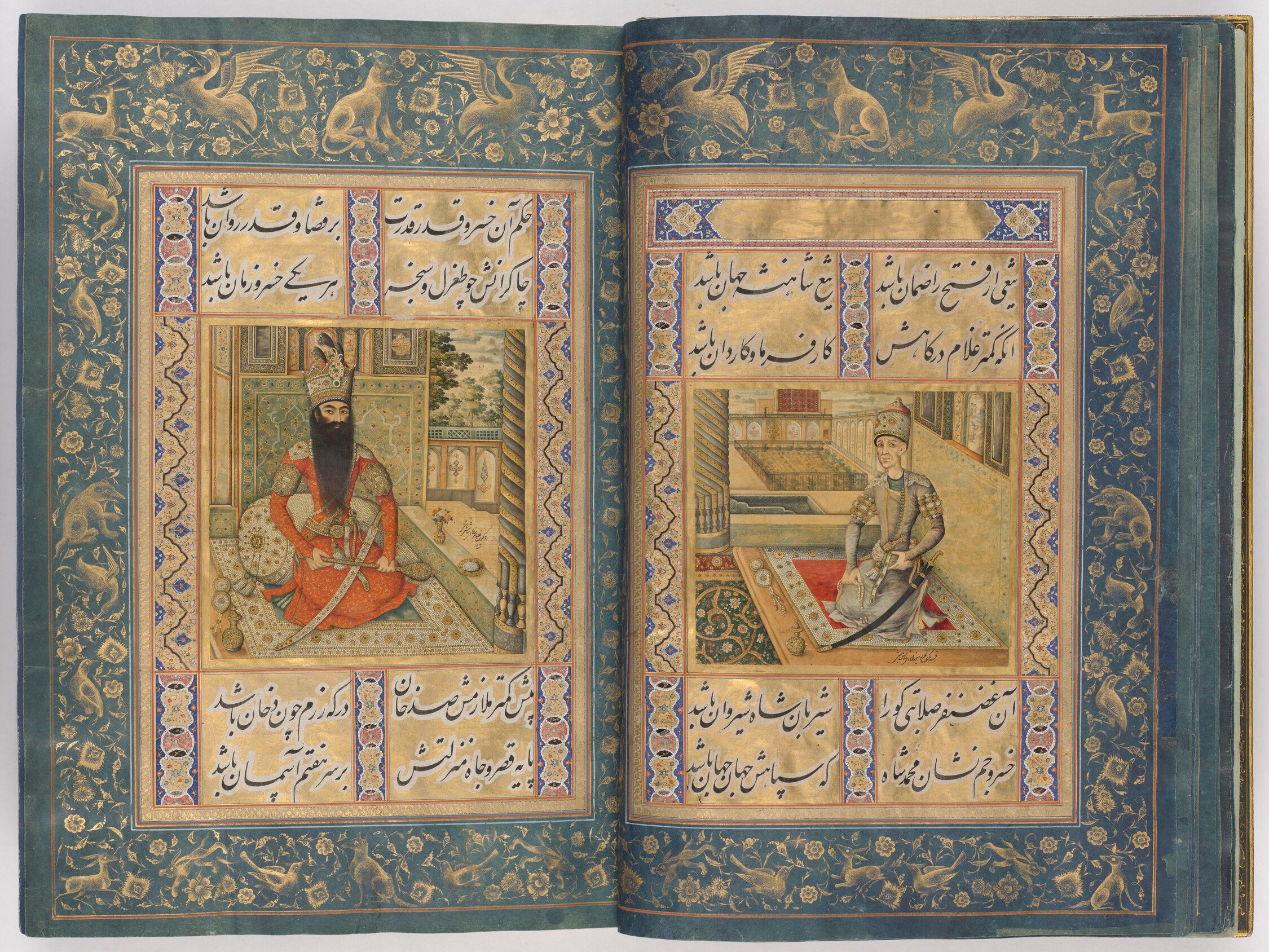

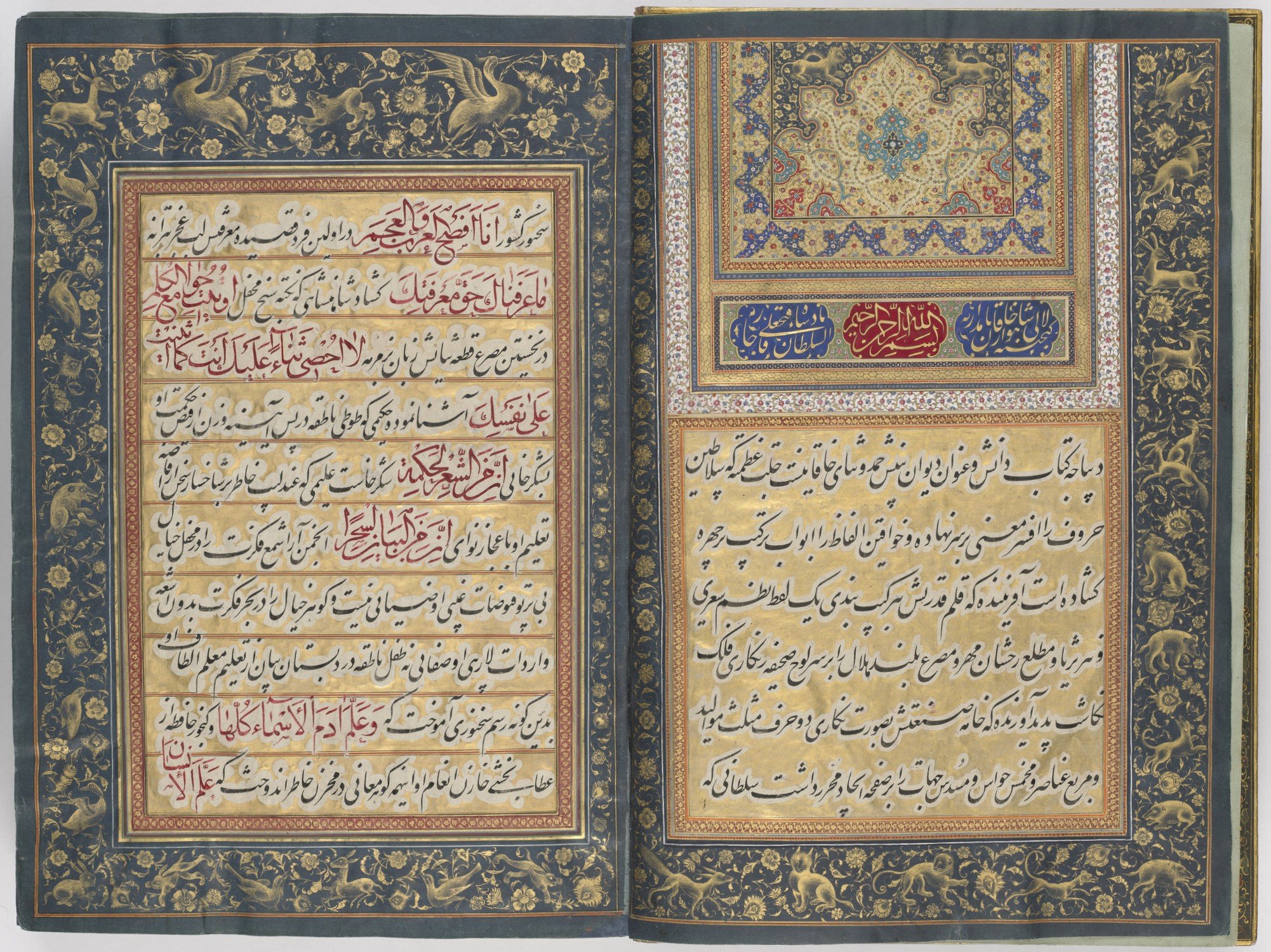

Divan-i Khaqan (The collected works of the Emperor)

Fath Ali Shah, the ruler of Persia (present-day Iran) from 1797 to 1834, wrote poetry under the penname Khaqan. He sent lavish copies of his Divan (Collected Works) as gifts to foreign sovereigns and dignitaries. This volume was written by the calligrapher, Muhammed Medhu al-Tehrani, in the nastaliq script – a cursive, calligraphic style that tends to slope downward from right to left. It represents the highest standards of contemporary Persian manuscript production. The script is highlighted with a solid wash of gold paint and set into dark-blue borders filled with glittering birds and animals.

Fath Ali Shah presented this magnificent manuscript to Sir Gore Ouseley in Tehran in 1811, along with several other gifts to the Prince Regent (later George IV).

Read more about the Divan-i Khaqan in our Collection Online.

How Watson Learned the Trick

How Watson Learned the Trick is a Sherlock Holmes story, handwritten by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle specially for Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House. Measuring less than four centimetres in height, it is one of over 170 handwritten manuscripts made for the Library, one of the Dolls’ House’s most remarkable rooms. The collection of tiny manuscripts was organised by Princess Marie Louise, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and the writer E. V. Lucas. They commissioned miniature books by some of the most famous literary names of the 1920s.

In Doyle’s charming short story, Watson attempts to learn Holmes’s art of logical deduction, but the famous detective proves him wrong on every point. Find out more about How Watson Learned the Trick in our Collection Online.

Aesop’s Fables

William Caxton was the first printer in England, establishing a press in the city of Westminster in 1476. Unlike his contemporaries, who produced mainly classical or religious works, Caxton printed popular stories, poetry and tales of chivalry for the English market. Many of these texts were translated by Caxton himself, either from Latin or French. This included the first English translation of Aesop’s Fables, an ancient Greek collection of tales, which Caxton printed in 1484. The book was presented to George III in 1773.