Artemisia Gentileschi

A closer look at Artemisia Gentileschi's life and art.

Reading time: 7 minutes

Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the greatest artists of her generation. Born in 1593 in Rome, she achieved success across Europe where her work was in demand amongst aristocratic and royal patrons. Artemisia challenged convention and defied expectations of women artists in 17th-century Europe.

I will show Your Illustrious Lordship what a woman can do

Life and career

Historically, the training routes open to male artists, such as apprenticeships, studying at an academy and copying artworks in public spaces, were not readily available to women. To become practising artists, women had to find other paths to artistic education, such as training with family members.

This was true of Artemisia, who was the daughter of the acclaimed artist Orazio Gentileschi. She trained in her father’s workshop in Rome, probably from the year she turned 16. Under her father’s tutelage, she adopted the tradition of painting from live models in the studio. Orazio was friends with the artist Caravaggio and was greatly influenced by him. Orazio embraced Caravaggio’s approach of combining realism with uplifting Baroque theatre, but his subjects tend to be more tenderly depicted.

When Artemisia was 17 and still working in her father’s workshop, she was raped by Agostino Tassi, an artist working with Orazio. Tassi falsely claimed that he would marry Artemisia and they embarked on a relationship. Around a year later, Orazio pressed rape charges against Tassi, probably in the hope of forcing the marriage or a payment of a dowry. The survival of the court transcripts show that Artemisia was subjected to torture under cross-examination. Tassi was eventually found guilty but his sentence of exile from Rome was not enforced.

After the trial, Artemisia left Rome for Florence where she further refined her art, and gained a reputation as a serious and well-regarded painter. In July 1616, she became the first woman to become a member of Florence’s Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing). This landmark life membership was fundamental for her career as it meant she was professionally recognised and had access to artistic networks previously only accessible to men.

Artemisia later worked in Naples and Venice before departing Italy for London in 1638, probably in order to help her elderly father complete the ceiling paintings at the Queen’s House in Greenwich (now in Marlborough House).

Orazio had been working at the court of Charles I and Henrietta Maria since 1626, and the King had been trying to attract Artemisia to London for several years by the time she left Italy. Within a year of Artemisia’s arrival in London, her father died. She continued to work at the English court until 1640, when she returned to Naples where she remained for the rest of her life.

Artemisia in the Royal Collection

Charles I was one of the greatest royal collectors of art, amassing a distinguished collection of works by renowned artists, including Raphael, Leonardo, Holbein, and Titian. But following his execution in 1649, which marked the end of the English Civil War, his art collection was sold. Learn more about Charles I's Lost Collection.

In the two major inventories of his collection, seven different paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi are listed. For many years, only one was considered to still survive – Artemisia’s magnificent Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (‘La Pittura’).

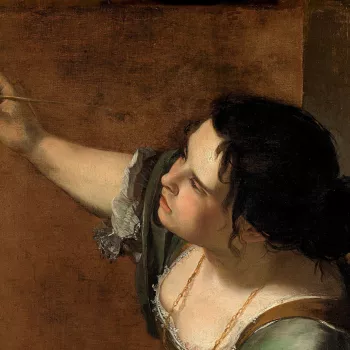

The act of ‘Painting’ (‘Pittura’) was traditionally represented in works of art in the form of a female allegorical or symbolic figure. The description of this figure comes from Cesare Ripa’s iconographic handbook Iconologica, published in 1593 and widely used by artists and poets in the Baroque era. Ripa describes ‘Painting’ as a beautiful woman with dark, dishevelled hair to indicate creative passion, a gold chain to show skill at imitation, and an iridescent shot silk dress to prove a mastery of colour.

In this bold, energetic painting, Artemisia demonstrates the practicality and physicality of the act of painting. She shows herself with sweat on her brow and an apron tied over her fine dress, the sleeves pushed up to keep them clean. She confidently shows herself in a way that none of her male contemporaries possibly could, as only a female artist could combine their self-portrait with the allegory of ‘Painting’.

Artemisia rediscovered

Recent work has revealed that another painting by Artemisia Gentileschi still survives in the Royal Collection.

Curators at Royal Collection Trust were working on the inventories of Charles I to match up the records with paintings in the Collection and elsewhere. This work revealed that a record of a painting of Susanna and the Elders in both the 1638–40 and 1649–51 inventories was a likely match with a painting that had been in store for many years. Find out more about the painting.

The painting was obscured by layers of discoloured varnish and heavy overpaint, which prevented any assessment of its true merits. A full cleaning, together with structural and restoration treatment, which included the painstaking removal of multiple non-original layers of paint, has revealed the brilliance of Artemisia’s original composition. During conservation treatment, a ‘CR’ (for Carolus Rex, latin for King Charles) brand was found on the reverse of the canvas, confirming the painting was in the collection of Charles I.

The painting’s history can be traced in a remarkably unbroken line, with records found in inventories from every century since its creation. In the 18th century, as Artemisia’s reputation waned, the painting appears to have lost its attribution. It was moved to Kensington Palace, where it is depicted in a watercolour of the Queen’s Bedchamber in 1819 leaning against a wall, suggesting it was considered the work of a minor artist and not worthy of hanging. It was later transferred to Hampton Court Palace, and in 1880 it was described as ‘in a bad state’ and sent for restoration, at which point additional layers of varnish and overpaint were likely applied.

The Biblical subject of ‘Susanna and the Elders’ describes the beautiful young wife Susanna, who is surprised by two men when she is bathing in her garden. They attempt to seduce her, threatening to blackmail her if she does not submit to their advances. Susanna refuses them and is faced with a false accusation of infidelity, punishable by death, before she is proven innocent. Her eventual acquittal is a clear triumph of truth and innocence.

In the painting, we are faced with the moment the Elders surprise Susanna as she descends into the water. The lecherous men appear very close over her shoulder, leaning on each other, looking at her body with lustful expressions. Susanna turns her body away, anxiously clutching a robe over her exposed nudity. Her vulnerability and discomfort are clear and she is at the mercy of both the onlookers in the painting, and the eyes of us, the observers.

Although it is perhaps a disturbing story for modern viewers to digest, ’Susanna and the Elders’ was popular among artists in the 16th and 17th centuries as a moral illustration of the victory of virtue over evil. It also provided an opportunity to paint a beautiful, naked woman for the appreciation of male patrons. Whilst Artemisia was not alone in painting the subject, it takes on a greater power in her paintings, where she seems to bring qualities of the female experience, and realities of the female body, to life.

One of the greatest artists of her generation

Until the 20th century, art historians did not typically focus on the work of women artists. Artemisia Gentileschi was no exception to this, but has received renewed critical attention since the mid-20th century, with recent exhibitions making her more of a household name.

You will find the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman

During her lifetime, Artemisia was well-known for her portraits but has become best known today for her powerful presentations of scenes from history and religion. The female subjects of her paintings include Cleopatra, Lucretia, Bathsheba, Judith, Diana and Susanna. These figures had been illustrated in art for many years, but Artemisia depicted them with much greater naturalism and empathy than her male predecessors and contemporaries.

It has been argued that the stories depicted by Artemisia may have held particular significance for her, given her own experience of sexual assault. Art historians have traditionally focused on Artemisia’s early life, and how that affected her depictions of women in distress. However, whilst it is tempting to draw direct parallels between Artemisia’s biography and her art, this cannot be at the expense of appreciating her great skill as a painter, her understanding of the human figure, and her abilities as a storyteller.