Collecting Italian Renaissance Drawings

By Lauren Porter, Senior Curator of Works on Paper

Reading time: 7 minutes

Charles II, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1660 to 1685, was the first British monarch to collect Old Master Drawings. Today, there are around 2,000 Italian Renaissance drawings in the Royal Collection, most of which were likely acquired during his reign.

Collectors in 17th-century England

It is likely that Charles II amassed his collection of drawings with the help of artists and notable courtiers. Artists at his court, such as John Michael Wright, were active as art dealers and may have procured drawings for the king. Charles II’s court painter, Sir Peter Lely, was also a prolific collector of drawings, reportedly owning the largest collection of drawings in Europe. Following his death, over 10,000 drawings were sold at auction, an activity which began to take place regularly during Charles II’s reign.

A handful of drawings from Lely’s collection, marked with a 'PL' stamp (his mark of ownership), are in the Royal Collection. They were probably acquired during the reign of George III from 1760 to 1820.

Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel

At the core of Charles II’s collection were drawings that had previously belonged to Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, the first great collector of drawings in England. Arundel, like other notable courtiers, began to form his collection during the reign of Charles II’s father, Charles I.

Arundel was a prolific buyer of artworks on his travels on the Continent. He deployed a network of agents across Europe to build up a remarkable collection of drawings, which were housed in more than 200 albums in Arundel House on the Strand in London.

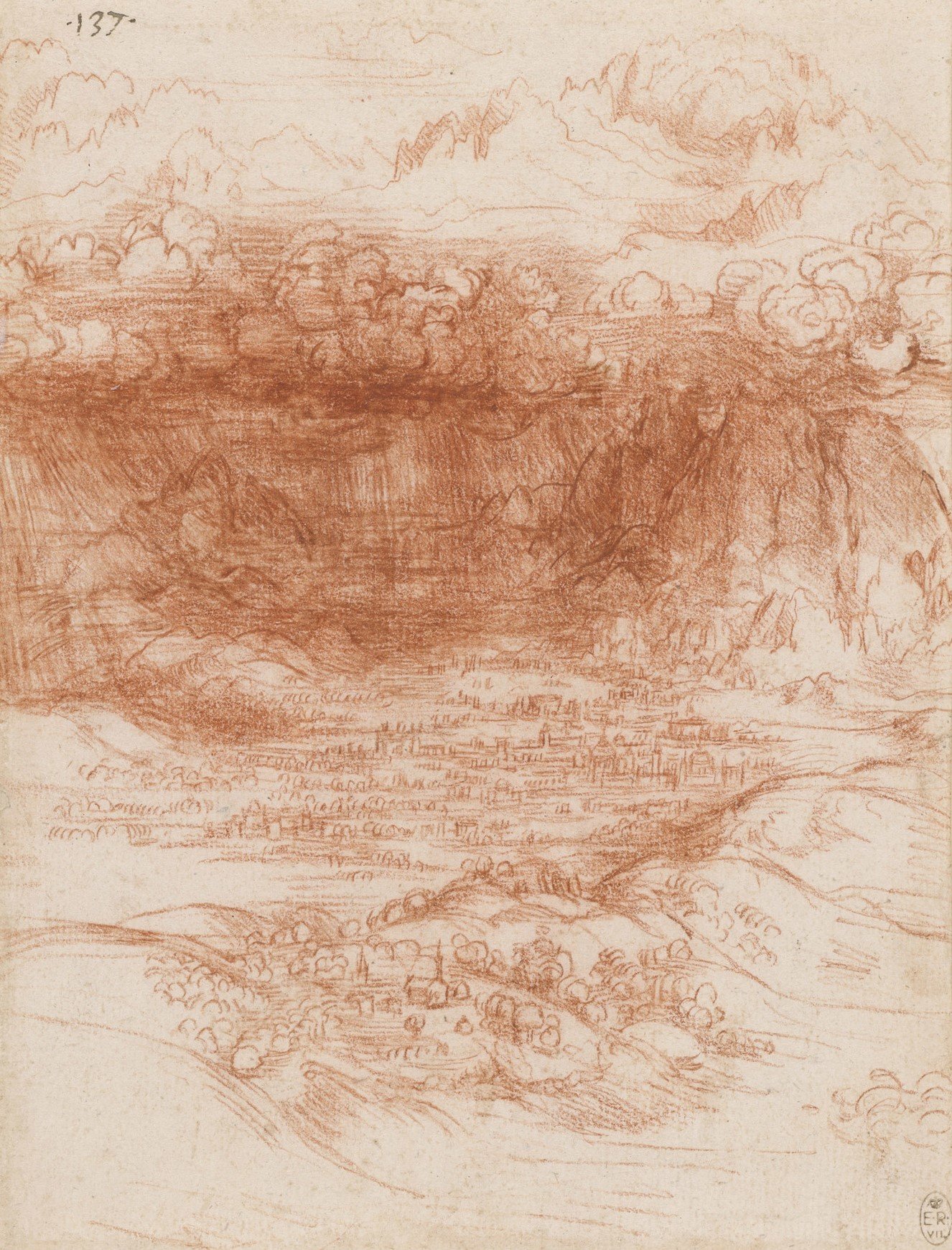

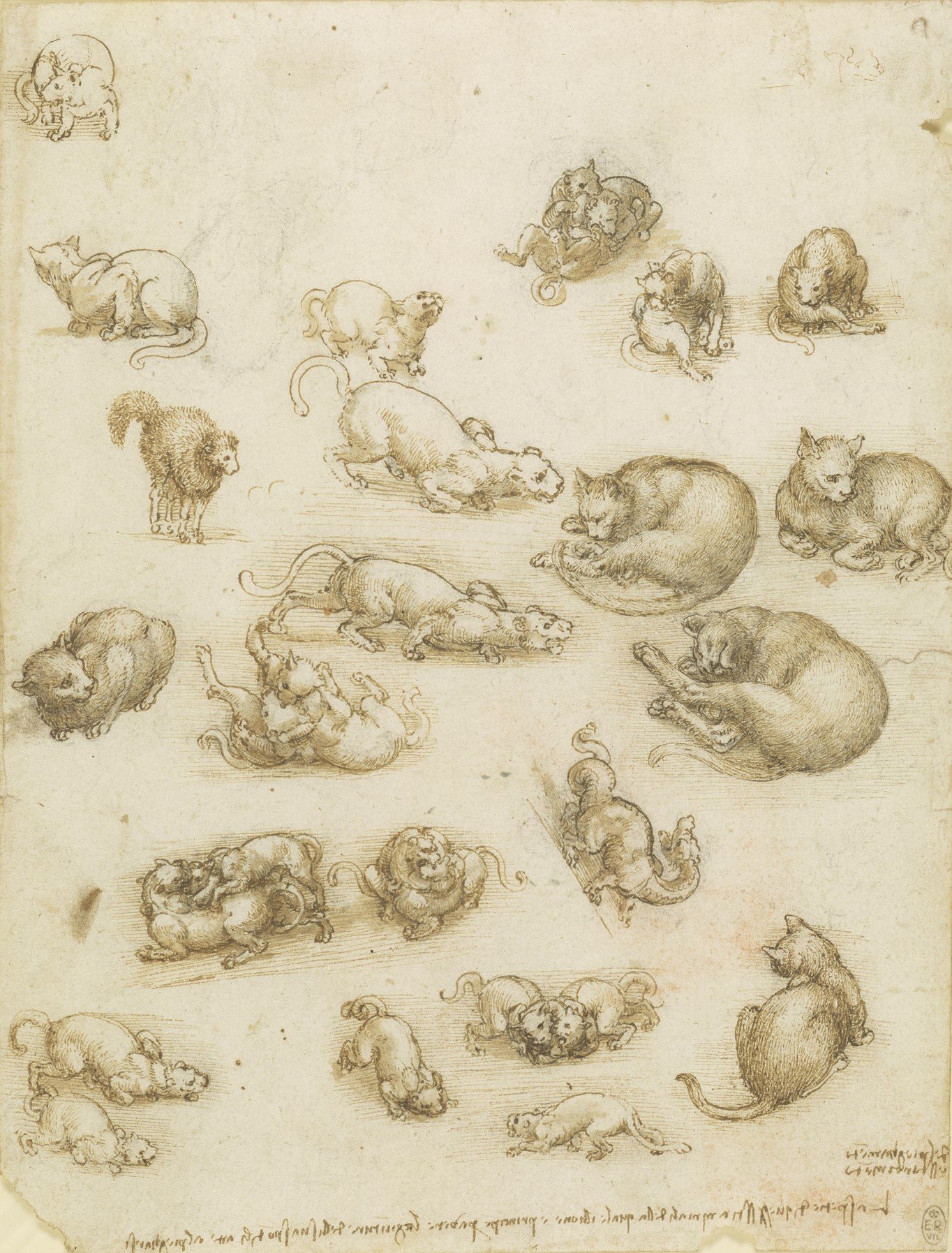

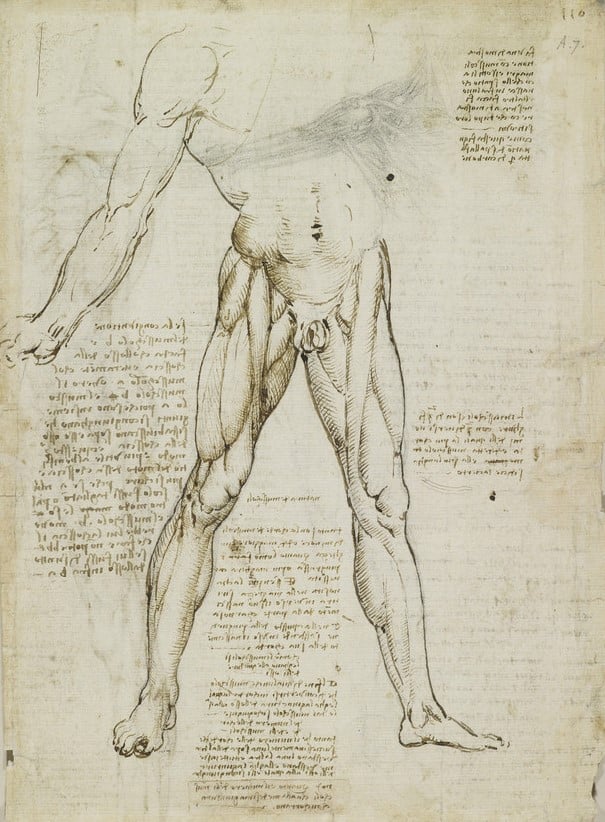

One of these albums contained 555 drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. This had previously been in the collection of Pompeo Leoni, the 16th-century sculptor. Leoni had acquired vast quantities of Leonardo’s drawings from the family of his former pupil, Francesco Melzi, who inherited some of Leonardo’s drawings. It is likely that the album was in England by 1626 and that it was in Arundel’s possession around 1630.

Later in the 17th century, Wenceslaus Hollar, an etcher, made prints after the Leonardos in Arundel’s collection. He inscribed two prints ‘ex Collectione Arundeliana’ (from the Arundel Collection), providing further evidence that this celebrated group of drawings were in Arundel’s possession.

Like many royalist supporters, Arundel went into exile in Europe during the English Civil War. While some of his collection accompanied him, it is likely that the Leonardo drawings remained in England. The Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 brought Charles II to the throne and saw the return of lands and titles to noble families. It is possible that Arundel’s grandson, Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk, presented Charles II with the drawings around 1670. The drawings by Leonardo are the single greatest acquisition of Italian Renaissance drawings in the Royal Collection and provide examples of his figure studies, botany, animal studies, and anatomical drawings.

Collectors' marks

Although there is little evidence to explain how Charles II’s collection was formed, there are physical clues on some of the drawings which help identify some of the likely sources of his collection.

Lanier ‘stars’

Another source of Italian Renaissance drawings were the collections of Nicholas Lanier and his uncle Jerome, who were both musicians at the royal court. They were also active in the art world.

Nicholas Lanier worked as an art dealer and travelled to Italy on at least three occasions. In the Royal Collection, 22 drawings connected with Nicholas Lanier are stamped in black ink with a small five-pointed star, and 14 drawings are stamped with a larger eight-pointed star. Examples include a drawing of Medea in her chariot after a work by Polidoro da Caravaggio. The five-pointed star is visible in the lower right corner, above the inscription ‘Pollidoro’, written in an elegant 17th-century hand– possibly belonging to Lanier.

A six-pointed star mark has been associated with Nicholas’s uncle, Jerome Lanier, and can be found on four drawings in the Royal Collection, including Taddeo Zuccaro’s The Conversion of the Proconsul. On two of the drawings, Jerome’s six-pointed star occurs with a ‘Jerom’ inscription, which reinforces the link between the stars and the Lanier collections.

In later centuries, it was common for collectors to stamp their drawings with a personal mark to identify ownership. However, this practice was not established in Lanier’s day, so the precise meaning of the star marks is not clear.

It is also uncertain how the Lanier drawings entered Charles II’s collection. During the Interregnum, a period of republican rule after Charles I’s execution in 1649, Nicholas Lanier was active as a dealer in Antwerp, Paris and The Hague. Lanier would have certainly crossed paths with the exiled Charles II, who spent time in all these places before his restoration in 1660. Lanier could have presented the drawings to the king back in England, following his reappointment as Master of the King’s Musick in 1661. Or the king could have acquired them after Lanier’s death.

At least 51 drawings in the Royal Collection bear inscriptions reportedly in the hand of the miniature painter, William Gibson, who was trained by Charles II’s court painter, Peter Lely. William was also a successful art dealer. The inscriptions typically give the name of the artist followed by two numbers. The numbers are price codes, the second being the unit: 1 for a shilling, 2 for half a crown (2 ½ shillings), 3 for a crown (5 shillings) and 4 for a pound (20 shillings).

This black chalk drawing of an an ideal head after Michelangelo bears the price code ‘2.4.’ It is also inscribed with Gibson’s attribution ‘Michol. Angollo Buonaroti’. This demonstrates that Gibson believed this drawing to be by Michelangelo himself, rather than a high-quality contemporary copy, justifying the relatively high price of £2. Read more about the copy of an ideal head in our Collection Online.

There is no evidence to suggest that Charles II purchased directly from Gibson. However, the drawings in the Collection bear no marks used by other collectors, suggesting a direct link between Gibson and Charles II.

Cutting corners

In this drawing of St Stephen by Parmigianino, an artist whose drawings were particularly sought after by English collectors, the top corners have been cut. This was probably so that it could be placed in a decorative mount. However, this style of cropping can also be found on many drawings in 17th-century English collections. It could either be the hallmark of an unidentified collector or part of a more general fashion. Like 13 other drawings in the Collection with cut corners, this drawing also features the Gibson inscription and price code on the verso: ‘F. Parmigiano 2.3’.

A further 29 Italian Renaissance drawings without collectors’ marks have been shaped in the same manner, including a beautiful red chalk drawing by Correggio of a sleeping Venus. This suggests that they too were probably acquired during the reign of Charles II.

The Italian Renaissance drawings acquired during the reign of Charles II form the foundation of the Royal Collection’s holdings today. The Collection has been supplemented during later reigns, with some Renaissance drawings acquired at auction for George III around 1760. The Earl of Bute acquired 10,000 drawings (mostly Italian Baroque) for George III from the collections of Cardinal Alessandro Albani and Consul Joseph Smith in 1762. But few Old Master Drawings have entered the collection since 1770.