Leonardo in the Royal Collection

A closer look at Leonardo da Vinci's works

Leonardo's Study of Anatomy

Why are Leonardo's drawings of the human body so revolutionary?

By Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings

Reading time: 7 minutes

Leonardo da Vinci trained as an artist in Florence, but when he moved to Milan in the 1480s his interest in scientific matters blossomed. As his career progressed Leonardo devoted ever more time to his researches – in particular the study of anatomy, with the ultimate aim of publishing an illustrated treatise on the subject.

In two campaigns of research, around 1490 and then between 1506-13, Leonardo investigated the nervous system, the internal organs, the bones and muscles, the structure and function of the heart, and the reproductive systems. Working in monastery hospitals and medical schools, he dissected perhaps thirty human corpses (and many more animals), recording his findings in hundreds of detailed drawings and many thousands of words of discussion and explanation.

Had he published his researches, Leonardo’s intended treatise would have been the single most important work on anatomy ever written. But his perfectionism, his difficulties in reconciling his observations with traditional beliefs, and simple bad luck prevented him from bringing his work to a conclusion.

At his death, Leonardo’s anatomical notes remained, unpublished, among his private papers. A later collector, Pompeo Leoni, mounted them in an album of mainly artistic drawings that entered the Royal Collection around 1670. In the late 19th century the anatomical drawings were finally published and the notes translated, and we can now understand Leonardo as one of the greatest anatomists ever to have lived.

Anatomical drawing

Leonardo’s study of anatomy began as part of his artistic work. The principal subject matter of the Renaissance artist was the human body, and to paint it correctly, the artist had to understand its structure. Artists in Italy witnessed dissections, and studied how the bones moved and the external forms of the muscles.

But from the outset Leonardo’s anatomical interests went far beyond what was immediately useful for an artist. He wanted to understand the phenomena of life – including the senses and emotions, the nervous system, the structure of the brain, and the mysteries of reproduction.

At this time anatomical illustration was in its infancy. To convey the three-dimensional form of the body and to show how it moves, Leonardo developed a range of illustrative techniques, borrowed in part from the fields of architecture and engineering. His challenges were in many ways the same as those faced by anatomists today, and some of Leonardo’s drawings are remarkably similar in approach to modern medical imagery.

Leonardo’s earliest studies

Human dissection was not prohibited by the Church, as is often assumed. Doctors occasionally performed autopsies to investigate the cause of a mysterious death, and public dissections – usually of executed criminals – were staged by the medical schools of Italy’s universities.

As a mere craftsman, the young Leonardo was not easily able to obtain human material for dissection. So at the start of his career he dissected animals instead, including frogs, bears, dogs, and monkeys – both as subjects in themselves, and in an attempt to map his findings from animals onto the human body.

Beyond the structure of the body, Leonardo wanted to understand the phenomena of life – including the senses, the emotions and reproduction. His earliest drawings record ancient beliefs about the body, often drawn in such a convincing way that we can believe that he had actually seen these fictive structures.

Skulls

In 1489 Leonardo was able to obtain a human skull. He cut it in various sections to investigate its structure, and recorded his findings on the pages of a small notebook, accompanied by exquisitely detailed drawings.

Leonardo attempted to infer the paths of the sensory nerves and the form of the brain. He regarded this knowledge as key to some of the topics that he wished to investigate, such as the emotions and the nature of the senses. But without an actual brain to dissect, the skulls alone could not provide that information.

Unable to make progress with his researches into the nervous system, Leonardo’s anatomical studies lapsed around 1490, and this first notebook was to languish, mostly empty, for almost 20 years.

Proportion and measurement

Around 1490 Leonardo also made a detailed study of human proportion. He was searching for the ideal form of the body, with each part a simple fraction of the whole – as depicted in his famous drawing of the ‘Vitruvian man’, showing a man in a square and circle, with his body divided into equal portions.

But when Leonardo began to measure a living model, he found that the truth was less simple. He was forced to express the proportions in twelfths, seventeenths and so on, and to ‘correct’ his observations to match the theory. Faced with the discrepancy between theory and reality, he soon abandoned these studies into human proportion.

During the same years Leonardo was working on a huge bronze equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, the former Duke of Milan. To construct the clay model accurately, Leonardo made measurements of horses in the ducal stables. The horse, unlike man, was not a ‘divine body’ and so Leonardo made no attempt to determine perfect and harmonious proportions – he simply recorded their dimensions in detail.

The Battle of Anghiari

In 1503 Leonardo was commissioned to paint a huge mural for the council chamber of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. The mural was to show a celebrated Florentine victory, the Battle of Anghiari – it was left unfinished and later destroyed, but it is known through early copies.

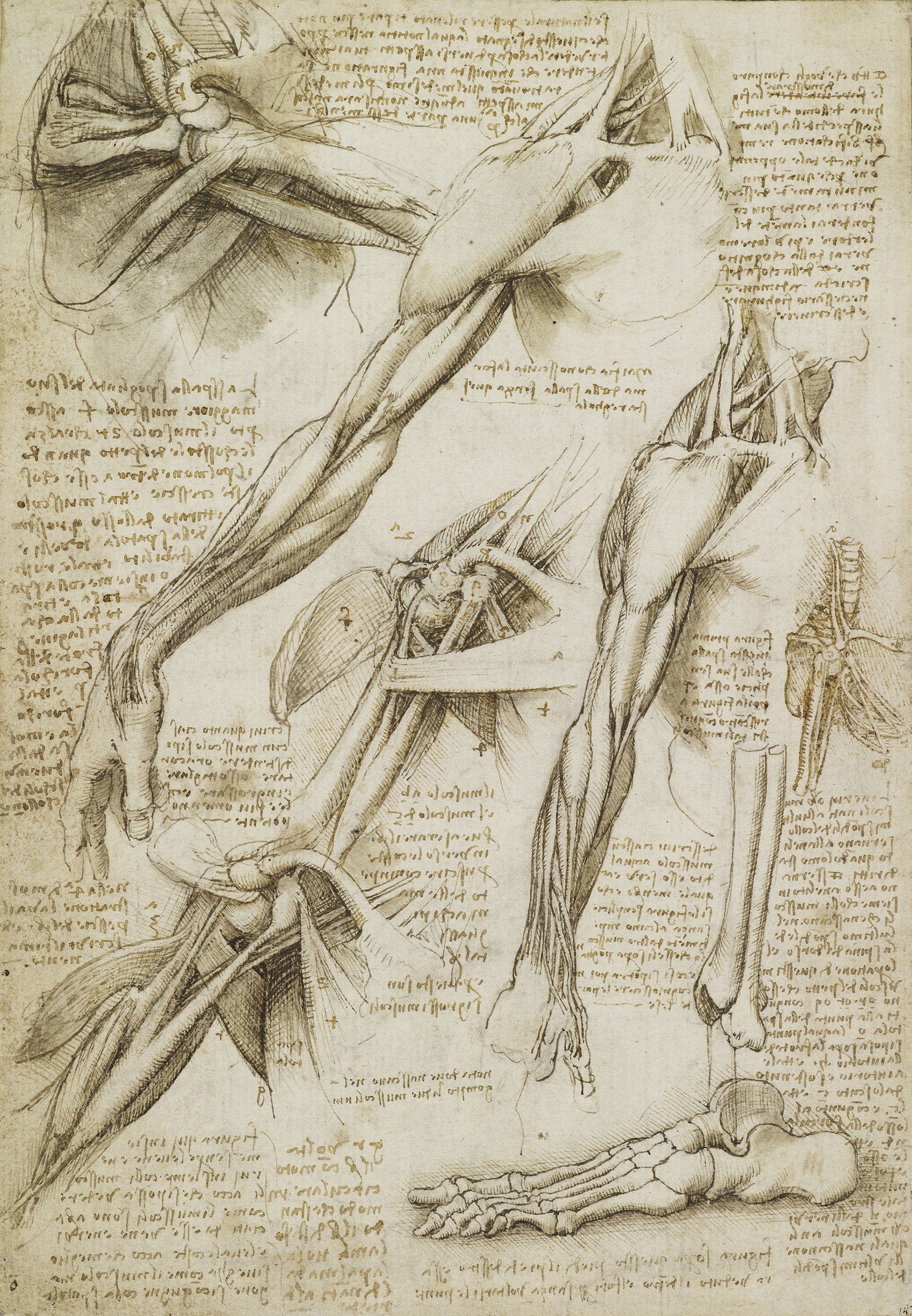

Leonardo’s composition centred on a furious cavalry skirmish, with men and horses in violent combat. The complex figures were to be over life size, and so Leonardo prepared meticulously for the project. He made many drawings of men both at rest and in action – in effect, a survey of the external musculature.

But as so often in his career, Leonardo was not satisfied simply with surface effects. He wanted to understand fundamental causes, what lay beneath the visual appearances. This project therefore led Leonardo back to the study of human anatomy, after a gap of 15 years.

The ‘Centenarian’

Leonardo was now in his fifties, one of the most famous artists in Italy, and his status and connections gave him the opportunity to conduct human dissections himself. His best-documented dissection was of an old man, probably in the winter of 1508.

Leonardo wrote in his notebook: 'This old man, a few hours before his death, told me that he was over a hundred years old, and that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness. And thus, while sitting on a bed in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, without any movement or sign of distress, he passed from this life. And I dissected him to see the cause of so sweet a death'.

Leonardo went on to describe the signs of coronary disease and cirrhosis of the liver. His detailed drawings of the old man’s internal organs – made in the same notebook that he had begun with the skull studies in 1489 – mark the beginning of five years of intense anatomical investigation.

Neurology

Now with access to human material, Leonardo returned to the study of the brain.

His earlier drawings had embodied the traditional belief that the brain contains three bulbous ventricles or cavities, arranged in a straight line behind the eyes. These were thought to house the mental faculties of perception, reasoning, imagination and memory. A rudimentary dissection would have shown him that the brain does indeed contain cavities, but not of this form.

In a brilliant experiment conducted around 1509, Leonardo injected molten wax into the ventricles to determine their true shape. Further dissections of the brain demonstrated that the nerves had no connection to the ventricles. He therefore abandoned the ancient belief that the ventricles housed the mental faculties.

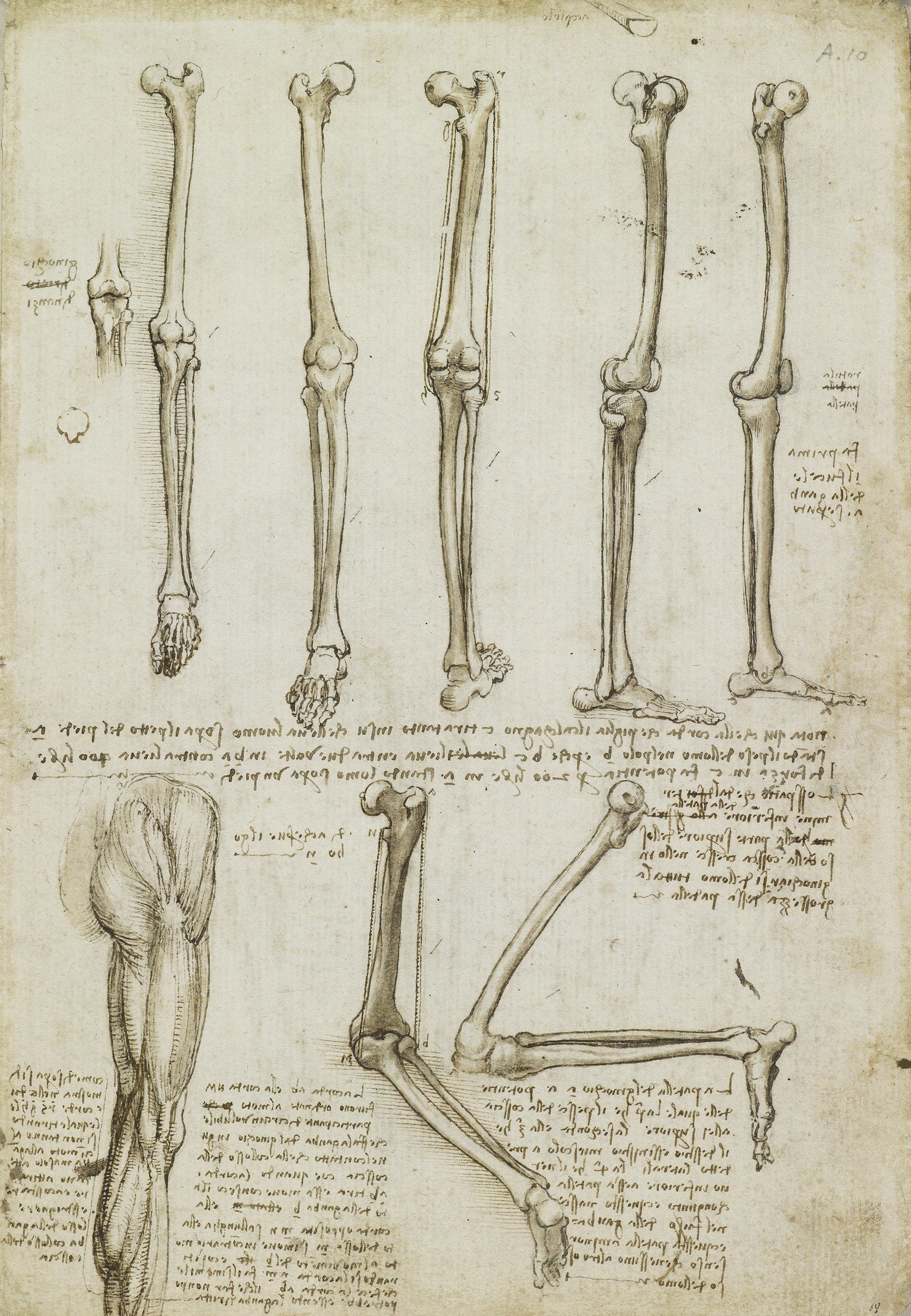

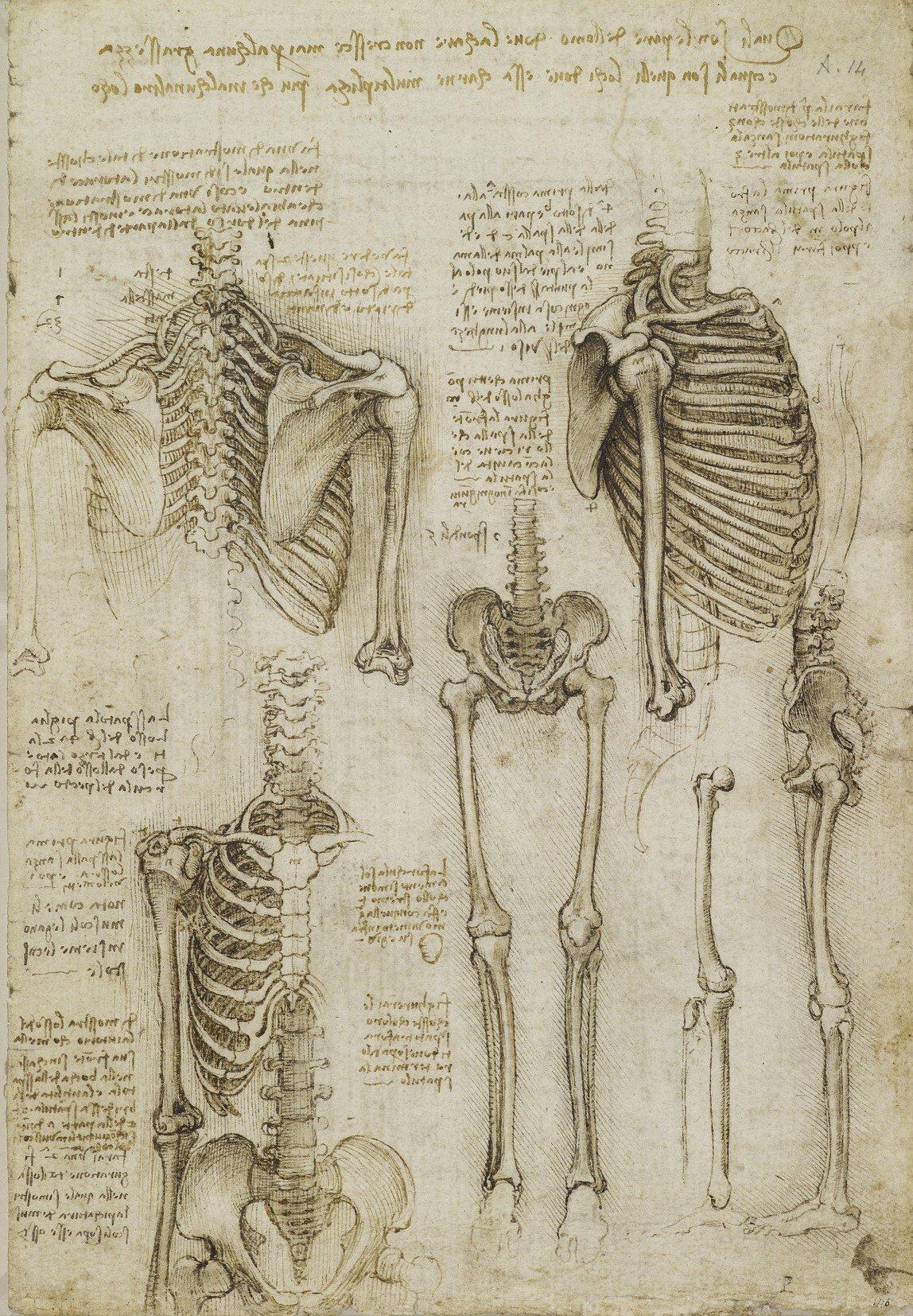

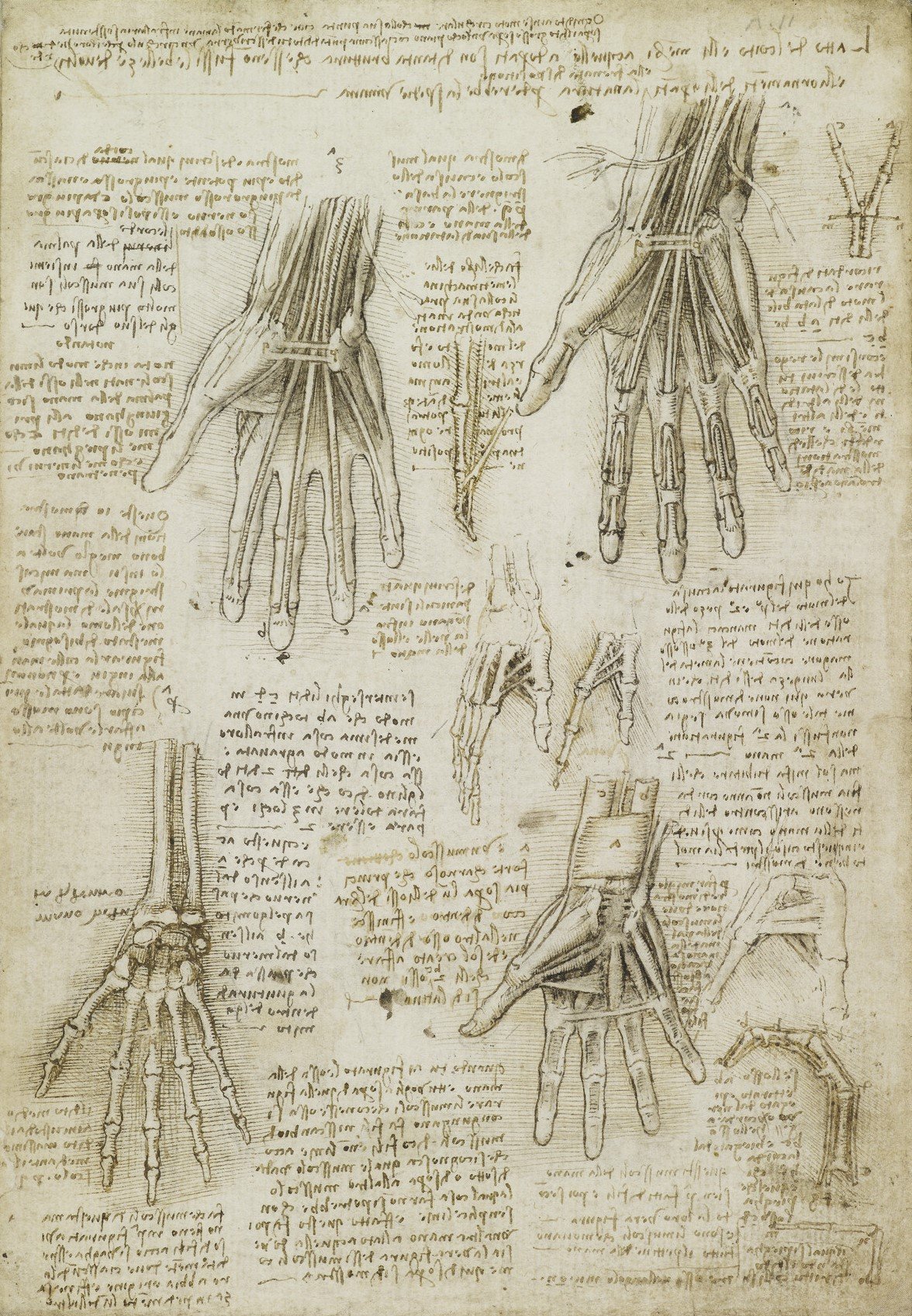

The bones and muscles

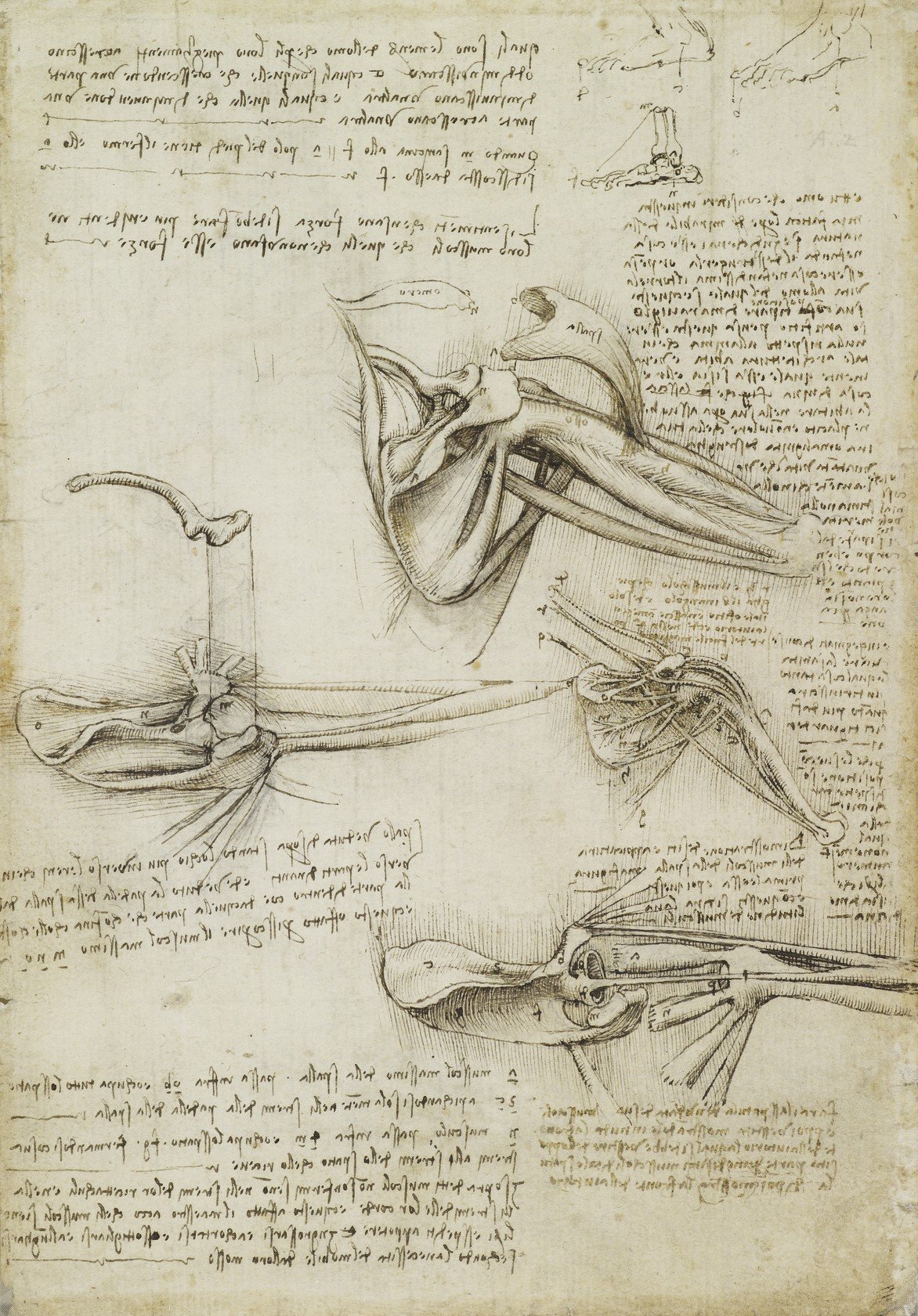

During the winter of 1510-11, Leonardo was apparently working in the medical school of the university of Pavia, south of Milan, alongside the professor of anatomy, Marcantonio della Torre. He now had ready access to human material and may have dissected as many as 20 corpses that winter. These drawings are now known as the 'Anatomical Manuscript A'.

Leonardo concentrated on the bones and muscles, analysing the body in purely mechanical terms, and adopting a range of illustrative techniques to make his drawings as clear as possible. He depicted the shoulder stripped down in stages, and the hand built up layer by layer. From engineering Leonardo took the convention of the ‘exploded view’; from architecture, the principles of elevation, plan and section, then dividing these angles more finely in order to depict the body from multiple directions.

Folios from Leonardo's 'Anatomical Manuscript A'

These illustrative conventions are now routine in modern medical imaging – we are so accustomed to them that it is difficult to appreciate the originality and brilliance of Leonardo’s innovations, more than 500 years ago.

Last Works

In 1511 Milan fell into military turmoil and Leonardo retreated to the country villa of his assistant Francesco Melzi. This was a period of calm during which he could have written up his earlier research for publication, but instead he was occupied with a variety of new interests. Though he had lost his access to human material, Leonardo continued his anatomical work, dissecting the corpses of birds, dogs and oxen.

Two topics engaged Leonardo at this time. The first was embryology, returning to his early interest in reproduction. Leonardo had dissected a pregnant cow a couple of years before, and now applied his findings to the human body. Perhaps his most famous anatomical drawing, showing a fetus curled up within an opened-out uterus, therefore includes bovine features such as a multiple placenta. Learn more about this drawing.

Leonardo’s final and most brilliant anatomical campaign was the study of the heart, based again on bovine dissection (though the heart of the ox is little different from the human heart). He described with great accuracy the chambers (the ventricles and atria) and the structure and functioning of the valves, and conducted experiments such as the construction of a glass model of the aortic valve. Leonardo understood that the heart was a one-way pump, and he came close to discovering the circulation of the blood.

But it was impossible to let go of ancient beliefs, such as the independence of the arteries and veins, and that the lungs served simply to cool the heart. Leonardo was unable to reconcile what he observed with what he believed to be true, and faced with apparently contradictory evidence, his brilliant studies of the heart came to an abrupt end.

The afterlife of Leonardo's anatomical studies

In September 1513, Leonardo moved to Rome. He tried to resume his anatomical studies at the hospital of Santo Spirito, next to the Vatican, but he was apparently accused of sacrilegious practices and prevented from performing any further dissections. In 1516 Leonardo moved to France to work as court artist to King Francis I and died in 1519 without returning to his anatomical studies.

Leonardo left his papers to his assistant Francesco Melzi. Though the anatomical drawings were remarked upon by all Leonardo’s early biographers, their dense and disorganised content was barely comprehended, and they were effectively lost to the world.

It was not until the late 1800s that Leonardo’s anatomical drawings were finally published and understood. By then their power to affect the course of anatomical knowledge had long passed. But their clarity and insight mark Leonardo out as one of the greatest scientists of the Renaissance.