Eastern Encounters

Drawn from the Royal Library's collection of South Asian books and manuscripts

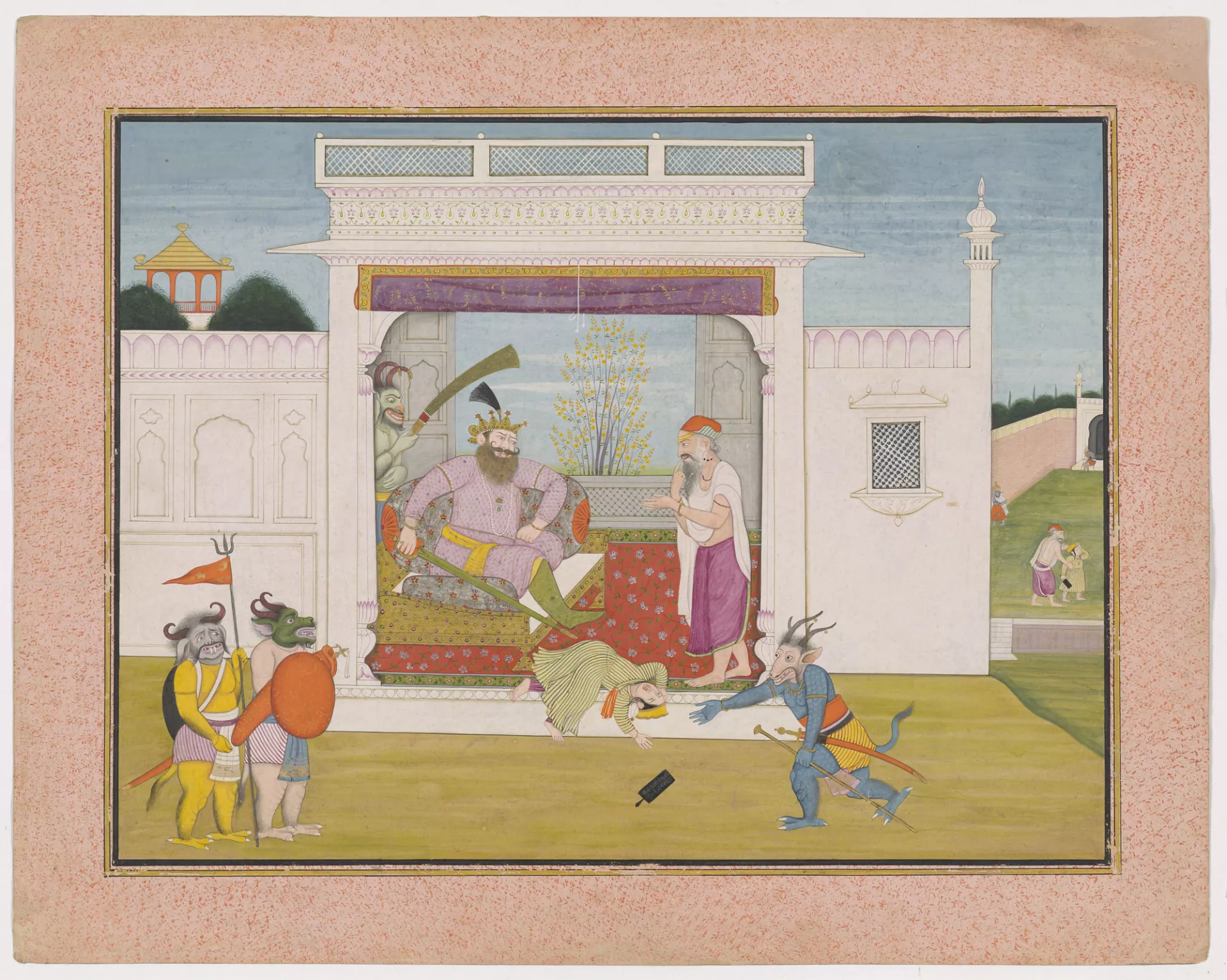

Folios from a series depicting the story of Prahlada from the Bhagavata Purana

Pahari, Nainsukh family workshop, <i>c</i>.1775–90Loose paintings in opaque watercolour including metallic pigments on paper with wide painted margins | 16 fols; 30.5 × 38.4 cm (average) | RCINS 925226–925241

The rajahs and nobles of the Pahari states often commissioned painters to create great series of works depicting Hindu religious epics such as the Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana ('Tales of the Supreme Lord'). The Royal Collection possesses 16 folios from a notable series of paintings telling the story of the boy Prahlada as told in the seventh book of the Bhagavata Purana. The paintings are numbered between 6 and 37 suggesting that there were at least 21 others in this series, although this figure is likely to have been even larger. The Bhagavata Purana narrates the stories of the avatars of Vishnu (see cat. no. 64). In the story of Prahlada, Vishnu protects the boy from his father, the demon king Hiranyakashipu who received a boon of immortality from the god Brahma. Hiranyakashipu entreated:

Make it so that I will not die because of any living being created by you. Neither inside nor outside, neither during the day nor at night, neither from any known weapon nor by any other thing, neither on the ground nor in the sky nor by any human being or animal. Neither lifeless things nor living entities, neither demigod or demon nor the great serpents may kill me. I must have no rivals, the supremacy in battle and the rule over all embodied souls including the deities of all planets. My glory must equal yours and never may the powers I have acquired by this yogic penance be defeated.

(Bhagavata Purana, 7:3:37–8)[188]

Vishnu eventually comes to earth in the form of Narasimha, the half-man half-lion avatar, in order to bring about Hiranyakashipu’s demise. The story teaches the importance of faith in God who will always come to the aid of his devotees and triumph over evil.

Although most Pahari artists did not sign their works, certain styles can be associated with family workshops. Much research has been carried out in relation to the family workshop of the early eighteenth-century artist Pandit Seu and his two sons, Manaku and the better-known Nainsukh.[189] Nainsukh’s four sons and two nephews were also all painters and their work is often stylistically attributed to the ‘first generation after Nainsukh’, to which this is confidently assigned.[190] A further generation of artists of the same family is similarly referred to as ‘the second generation after Nainsukh’. The refined family style is characterised by delicate lines and precise brushwork, a fresh palette and mastery of colour, closely observed detail and a range of skilfully rendered, expressive characters. In their brilliant compositions, wonderful sense of action and humour, the paintings of the Nainsukh family workshop are unique in the history of South Asian art. Their works remained remarkably constant despite the migration of the painters to different states within the Pahari region.[191]

Unlike Mughal paintings, the works of Pahari artists were not usually bound into albums but kept loose, each protected by a cover sheet. Many of the Pahari hill kingdoms did not survive into the twentieth century and their collections were dispersed, often turning up in the bazaars of the cultural capitals of Amritsar and Lahore. Series of paintings were regularly broken up as they were sold on to collectors, and their colophon leaves often lost, with the result that few retain dates or inscriptions. It is extremely rare for one collection to have so many paintings from a single sequence.

[188] Srimad Bhagavatam, Canto 7, chapter 3, verses 37–8.

[189] For these artists, see Goswamy and Fischer 1992, pp. 211–67 and Goswamy 1968.

[190] For these artists, see Goswamy and Fischer 1992, pp. 307–66.

[191] Members of this family of artists are known to have migrated from their home state of Guler to Kangra, Chamba, Basohli and Mandi among others. See Goswamy and Fischer 1992, pp. 308–17.

Bibliographic reference(s)

Am I visible?