Eastern Encounters

Drawn from the Royal Library's collection of South Asian books and manuscripts

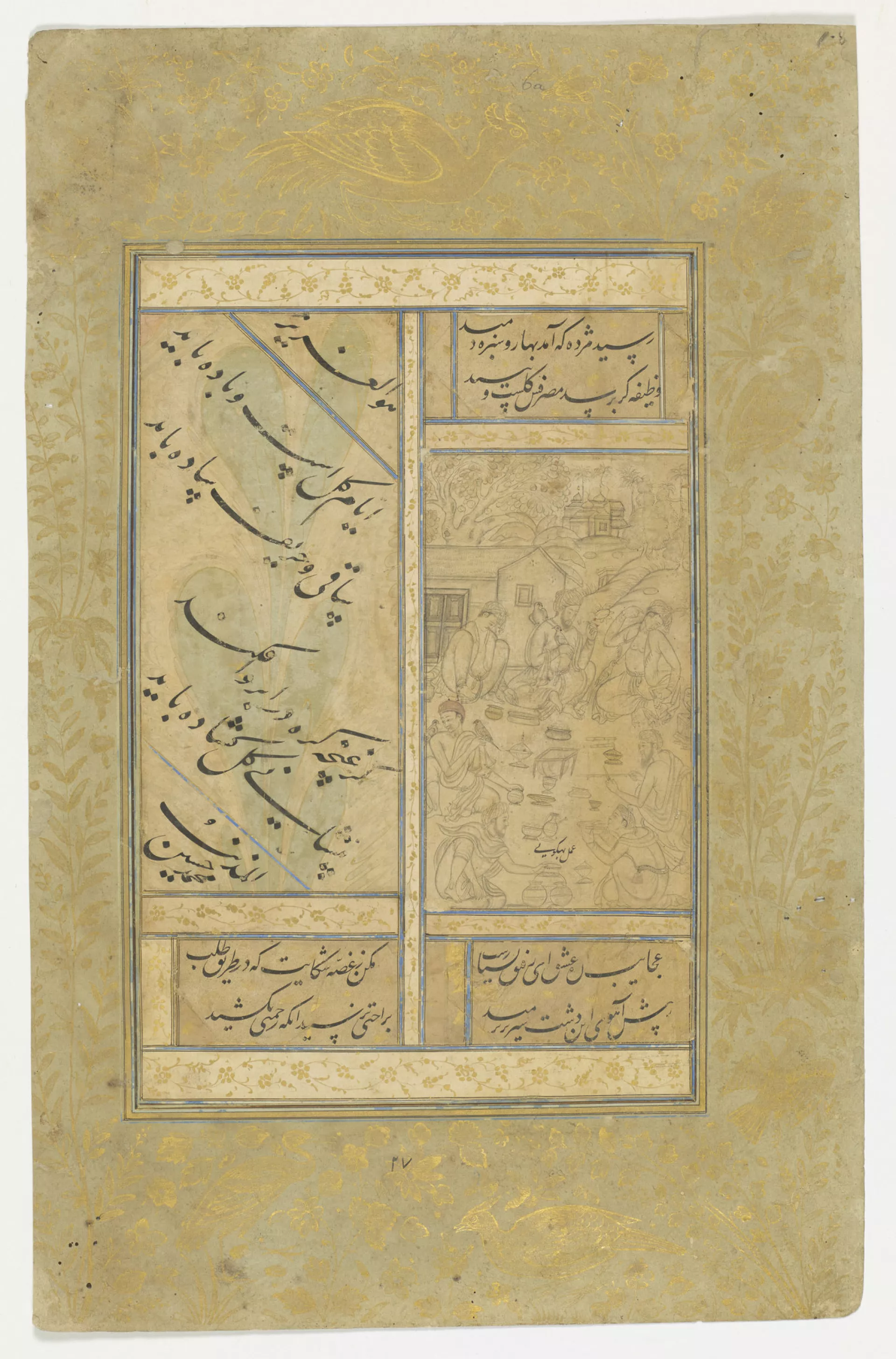

Folios from an early Mughal album of calligraphy and paintings

Mughal <i>c.</i>1600Unbound composite pages of specimens of calligraphy and paintings; set into borders of gold metallic paint on dyed papers | 23 fols; 37.0 × 23.9 cm (average) | RCINS 1005039; 1005042–1005049; 1005050–1005064

The Persian name for an album of paintings and calligraphy is muraqqa’. Derived from the Arabic word for ‘patched’ or ‘patchwork’, the term reflects the collage-like quality of an album in which each page is made up of several sheets of paper, cut up and arranged within decorative borders.[9] The assembling of a muraqqa’ was a deliberate exercise of connoisseurship. The finest examples combined the works of past and contemporary master calligraphers and painters, with each opening inspiring literary, philosophical and art historical dialogue. The following folios are from a muraqqa’ assembled at the Mughal court c.1600. The group of 23 folios entered the Royal Collection as loose leaves, but Persian numerals inscribed at the top-left corner of each indicate that the album originally contained at least 76 leaves. A further 37 folios from what appears to be the same muraqqa’ are known to survive in other collections.[10] Because of its dispersal, the album’s original construction and nuances of purpose have been lost.

Contemporary writers highlighted the abstract power of the word, each letter ‘a black cloud pregnant with knowledge; the wand for the treasure of insight’.[11] Paintings were similarly considered in semiotic terms: ‘an image leads to the form it represents and this [leads] to the meaning’.[12] European paintings and prints were known to Mughal artists (‘in general they [Europeans] make pictures of material resemblances’),[13] but given that realism and naturalism were not principal concerns of Mughal artists, it was the allegorical elements of European images which had most resonance, leading ‘those who see only the outside of things to the place of real truth’.[14] Despite the criticism of more orthodox members of his court, the Emperor Akbar fully supported the creation of figurative imagery, stating that ‘there are many who hate painting; but such men I dislike. It appears to me as if a painter had a quite peculiar means of recognising God.’[15]

The majority of calligraphy specimens in this album were written by the calligrapher Muhammad Husayn of Kashmir (see also cat. no. 1), but among the others are works by the great fifteenth and early sixteenth-century master calligraphers of Iran and Central Asia including the famous Mir Ali of Herat (d. 1544). The paintings mostly date to the end of the reign of Akbar when the Mughal court was based at Lahore. They are distinctive in that they were drawn in a style that has subsequently been termed nim-qalam (‘half-pen’). In contrast to most Mughal paintings in which sparse outline drawings are built up with multiple layers of opaque pigment, these are effectively line drawings. Minimally coloured with light washes, they produce a remarkably different visual effect with much of the page left blank. The artists’ and calligraphers’ names are inscribed at the bottom of each image or calligraphic panel. For the paintings, these are third-person ascriptions rather than signatures, but most likely date to when the album was compiled and include some of the most celebrated masters of Akbar’s painting atelier. When Mughal artists or calligraphers signed their own work they almost always preceded their name with a word or phrase of humility such as al-abd or banda, both implying a ‘slave’ or ‘servant’ creating in the service of God. In ascriptions, however, the artists’ names are simply preceded by amal-e meaning ‘the work of’, or, in the case of senior artists, the title ustad (‘master’).

The extravagantly illuminated borders of these folios are made up of two separate sheets of paper stuck back to back so that some folios have sides of different coloured borders, either plain or dyed blue or green. They are all painted in gold pigment to produce a brilliant sensation of warm lustre. To create the gold pigment, Mughal artists ground sheets of gold leaf to fine particles in a solution of water and sand or honey. The particles were then mixed with a binding medium, such as gum arabic, to yield the fluid, versatile pigment. The gold designs of the borders are all unique, created without mechanical reproduction. Some comprise dense floral patterns while others incorporate delicately dispersed stylised blossoms and leaves. Many feature wild birds or fantastic beasts hunting prey. Thin rulings in gold, green, red and blue create frames to skilfully camouflage the edges between pieces of paper. A wide variety of papers was produced in Hindustan, including those with a marbled effect, described in Persian as abri, meaning ‘clouded’. Many of the verses in this album are written on such marbled, gold-flecked paper which produces the magnificent effect of the words floating in a glittering sky. To create the gold flecks, the paper was sprayed with gold pigment. For larger flakes, the paper was brushed with a dilute rice starch paste or dilute gum arabic onto which flecks of gold leaf passed through a mesh were burnished flat to stick to the surface, the varying degree of fineness of the mesh controlling the size of the flecks.[16]

[9] See Wright ed. 2008, p. xvii.

[10] During the 1960s, these other folios were in a private collection in Europe, bound in a Qajar binding. 32 folios (73 pages), made up of specimens of calligraphy only, were sold as a group at Sotheby’s in 1995 (18 October, lot 68), and are now in the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha. Five other folios, four of which have paintings, were sold at Christie’s in 2007 (17 April, sale 7389, lots 211–215 and 218) and Christie’s in 2012 (26 April, lot 12). The presence or impression of a textile guard grip and sewing holes on many of the Royal Collection folios are evidence that they were originally bound. Within this group, it has been possible to establish a coherent ordering through a pattern of insect damage and page numbers.

[11] Ain-i Akbari, vol. 1, p. 103.

[12] Ibid., p. 102, edited translation quoted in Koch 2010, p. 27.

[13] Ibid., p. 103, edited translation quoted in Koch 2010, p. 27.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ain-i Akbari, vol. 1, p. 115. There have been periods of iconoclasm throughout Islamic history: Shah Tahmasp of Iran (r. 1524–76) was a keen patron of painting in his early years but turned against it for ostensibly religious reasons in later life.

[16] For the use of gold in Mughal paintings and manuscripts see Chowdry 2017.