The Macartney Embassy: Gifts Exchanged between George III and the Qianlong Emperor

An eighteenth century diplomatic mission yielded exquisite gifts

In the late eighteenth century, China and Britain were worlds apart. The British East India Company had been trading with Chinese merchants for 200 years, but in a strictly limited way. Foreign trading bodies were only allowed into the port of Canton (today Guangzhou) for five months of the year and all trade had to be carried out through Chinese officials who imposed high taxes on foreign trade.

In 1792, George III (1738–1820) sent an Embassy headed by Earl Macartney of Lissanore (1737–1806) to China in an attempt to negotiate a preferential treaty of commerce and friendship with the Qianlong Emperor (1711–99). Among his requests were the establishment of a British ambassador at the Court of Peking, improved trading conditions in Canton and access to new ports to expand British trade. Members of the Embassy included Macartney’s secretary George Staunton (1781–1859), as well as a watchmaker, a mathematical instrument maker and a ‘Machinist’, whose role was to explain the scientific instruments to the Chinese. Two illustrators and a botanist were also brought along for the secondary aim of the Embassy: the gathering of information.

As part of this mission, the Embassy departed Britain bearing gifts intended both to showcase British scientific achievement and to encourage interest in British trade with exotica such as amber, coral and ivory and European manufactures including cloth from Bolton, brass from Birmingham and linen from Ireland. In response, the Qianlong Emperor gave gifts not only to George III but also to all members of his Embassy. The gifts given exhibited local material and manufacture as well as exquisite workmanship. Many of the objects given by the Qianlong Emperor to George III would later influence the tastes of his son the Prince of Wales (1762–1830).

However, the mission failed to achieve its trading aims. In the eyes of the Chinese emperor the British had come to pay tribute to him rather than to establish diplomatic relations as understood in the West. In a lengthy edict addressed to George III, the Emperor refused to allow a permanent British mission to Peking, which was ‘a request contrary to our dynastic usage’. When presented with the king’s gifts, which included a Herschel telescope, a planetarium, artillery pieces, air pumps and carriages, as well as Wedgwood pottery, chandeliers, clocks and watches, he declared:

I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.

Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor was not alone in his absence of interest in the gifts: Lord Macartney described the objects received from the Chinese in his journal as, 'consisting of lanterns, pieces of silk and porcelain, balls of tea, some drawings, etc. don't appear to me to be very fine, although our conductors affect to consider them as of great value'. At this time Chinese porcelain and silks could be easily acquired in Britain, although red lacquer objects, still imbued with a degree of novelty, were later displayed in the Green Closet at Frogmore House. Many of the gifts were sold at auction as part of Queen Charlotte’s estate after her death in 1818 and only some of these were later reacquired by George IV.

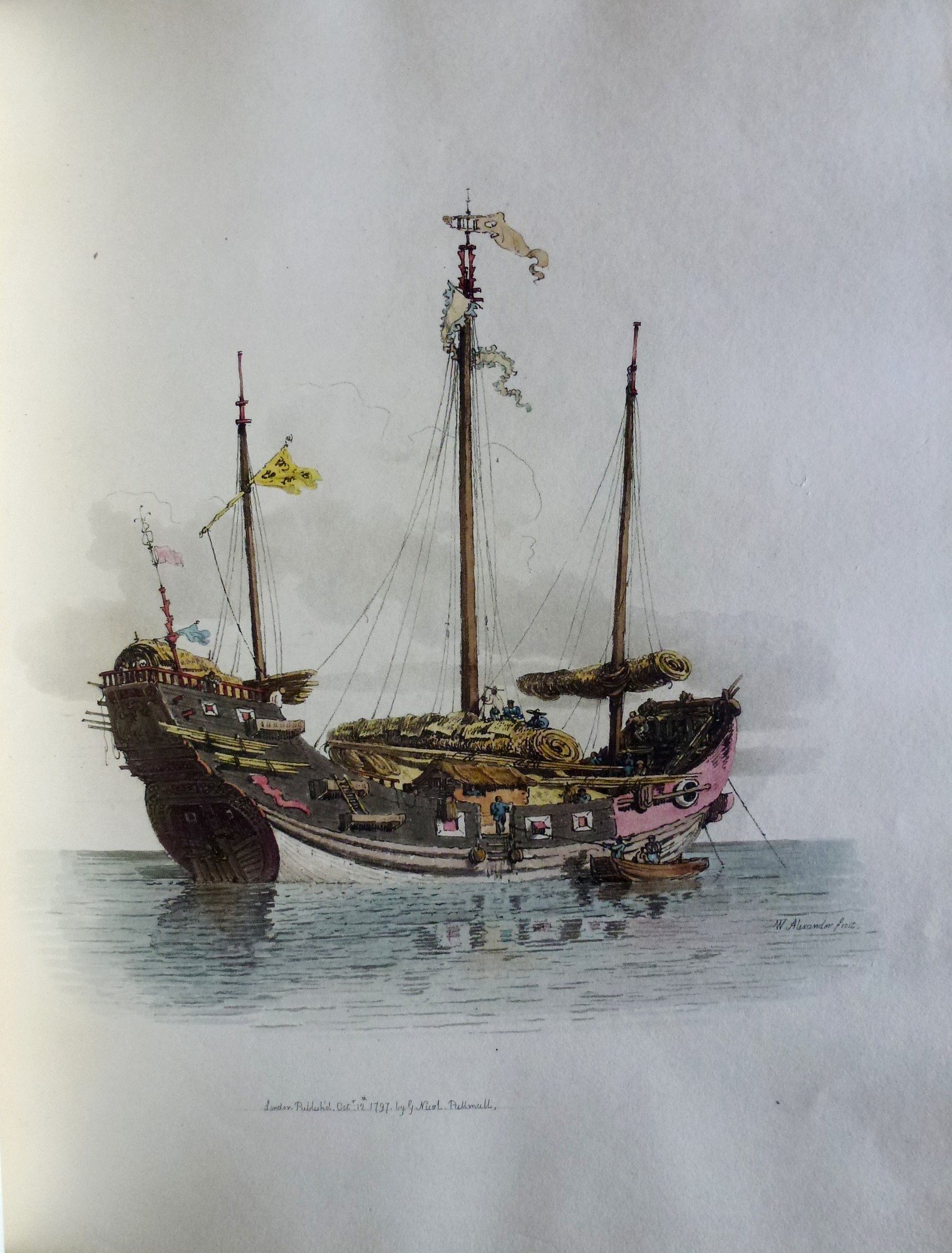

Despite its diplomatic and economic failures, the Embassy did much to demystify British perceptions of the East. Prior to the Embassy, the British had relied on second-hand accounts gleaned mostly from Jesuits and other missionaries. However subsequently, William Alexander, one of the Embassy’s illustrators, published a series of hand-coloured engravings depicting the Chinese Court as well as scenes of everyday life in China. In addition, the return journey from Peking to Canton enabled Macartney and his men to gather botanical, agricultural and geographical information. Macartney wrote in his journal:

We are now masters of geography of the north east coast of China, and have now acquired a knowledge of the Yellow Sea which was never before navigated by European ships.

Lord Macartney