Book conservation: The Eikon Basilike

Study of this book can tell us much about its origins

Identifying the origin of the ribbons

The process of rebinding the book revealed clues as to the reliability of the claim that the ribbon attached to the boards was one which belonged to Charles I.

The ribbon is of the right colour to have been a Garter ribbon, and at 10 cm wide and, when each piece is laid end to end, 136 cm long, it has appropriate dimensions.

When a tiny, detached fragment of silk was sent for radiocarbon dating the results indicated that it was made between 1631 and 1670.

We know that not only is it plausible for the fabric to have been a Garter ribbon, but also that the silk dates from a time contemporary with Charles I.

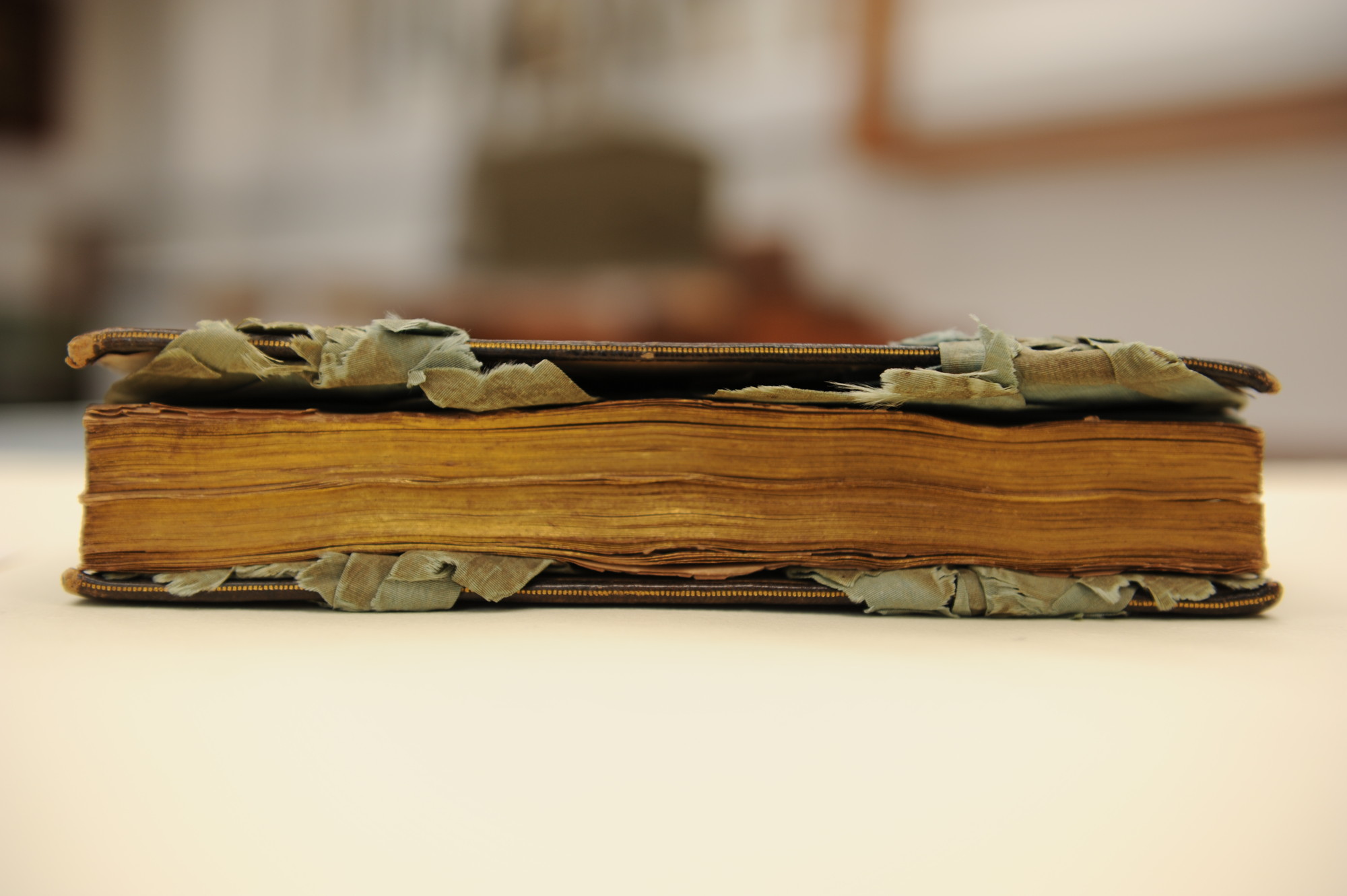

Conservation work showed that the ribbons were attached to the book by puncturing the boards and pushing the silk through the holes. The ends of the ribbons were then spread out and flattened inside the book’s front and back covers before the endpapers were pasted down on top.

It appears that the endpapers are the original ones and there are no tears in them, which there would be if the endpapers had been unstuck, lifted to allow the insertion of the ribbons, and pasted down again.

There is no indication that the book has been conserved before now, mending any tears in the endpapers or replacing them. The style of the binding suggests that it is contemporary with the date of publication in 1649. Adding the ribbons and pasting down the endpapers shortly afterwards would indicate that the silk was known at the time to be special.

The ribbons serve no practical function. They are inappropriate to the design of the book, so it is reasonable to think that they were added in order to display them. The book being the Eikon Basilike, a text so strongly supportive of Charles I, implies a close link between the ribbons and the executed King.

Indications of how important the lengths of ribbon were deemed to be have been revealed through observations made by the conservators about the process of the original binding work.

While the gold tooling on the covers of the book is elegant and skilful and the binding in general is of high quality, the conservators observed that the endpapers had to be cut to allow the book to open. It is unlikely that a professional seventeenth-century bookbinder would have made such a mistake.

Furthermore, it would be surprising if a binder of the skill shown in the rest of the book’s structure and decoration did not make allowances for the extra space taken up by the ribbons being in the boards and adapt the book accordingly. No such allowance was made, hence the need for extensive conservation work on the book today. An explanation for this could be that the binder did not know that the ribbons were to be added. Perhaps the book’s original owner instructed the binder to leave the endpapers unstuck so that the lengths of ribbon could be inserted privately at home.

This degree of caution might suggest that the owner believed that the silk had belonged to the King. Perhaps the lengths of ribbon were too precious, or too controversial, to allow the binder to see.