Holbein in the Royal Collection

A closer look at Hans Holbein's works.

Derich Born

A closer look at Holbein’s remarkable painting.

By Nicola Christie, Head of Paintings Conservation

Reading time: 5 minutes

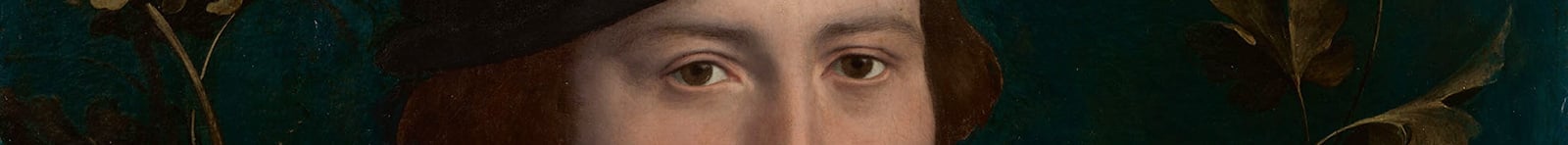

One of Hans Holbein’s most striking painted portraits in the Royal Collection is that of Derich Born. Derich Born was 23 when Holbein painted this portrait. The painted inscription on the ledge below the sitter suggests that Holbein was proud of his work. As the artist himself wrote in the top line of the Latin inscription:

If you added a voice this would be Derich his very self

Holbein used materials and pigments that would have been familiar to any 16th Century European painter but employed them with a skill and inventiveness that made him the most sought-after portraitist at the English court.

Who was Derich Born?

Derich Born was one of the German merchants who lived and worked together in the Steelyard in the City of London. He traded in a variety of goods, ranging from weapons to towels. Holbein painted a number of these German merchants during his second stay in England, seven of these paintings survive. His portrait of another merchant, thought to be Hans of Antwerp, is also in the Royal Collection.

How was the painting created?

The painting is on two boards of oak from the Baltic region, joined down the middle and prepared with a chalk ground. Baltic oak was the most commonly used support for painting in England during this period and a join in a panel painting of this size was common. The central position, however, in uncommon. On top of the chalk ground he applied a thin grey priming layer in broad multi-directional brushstrokes which contributes to the cool tonality of the painting. It provides an interesting comparison with the relative warmth of Holbein’s portrait of William Reskimer which is painted on a pink priming layer.

The portrait was drawn on the prepared panel with a carbon-containing pigment and probably applied with a brush. Although no preparatory drawing survives for Derich Born, it is probable that one was made and used to transfer the main elements of the figure to the panel.

Infrared reflectography allows us to look beneath the painted surface and examine the carbon-based underdrawing. The changes to Derich’s face can be seen clearly. At both underdrawing and painting stages Holbein revised the contours, notably in the searching lines which define the sitter’s cheek and jawline.

Holbein’s materials and skill

Derich’s black garments are created in simple mixtures of lamp black and lead white bound in linseed oil. Here we see Holbein’s skill in recreating fabric and texture in paint. The superbly executed black silk sleeve is painted with smooth, almost imperceptible brushstrokes to create the effect of light falling on the fabric. The short-haired black fur, painted in the same paint mixture as the silk is more loosely applied, using a stiffer paint with a square-tipped brush and dragging the highlights into the still wet dark paint.

The intensely-coloured blue background is painted in two thick layers of the highest quality azurite, a deep-blue mineral. After the first layer, Holbein adjusted the right contour of the figure and the different textures of the two layers can be seen quite clearly.

The paint was so thick it created a raised edge around the contour of Derich’s figure, which dribbled just a tiny amount as it dried yet never disturbed the perfect contour.

Recent conservation, undertaken in partnership with the Getty Conservation Institute, revealed the clear imprint of a thumb – probably Holbein’s – at the left edge of the panel, suggesting that the paint may have taken longer to dry than he expected.

The plum tones of the stone ledge include an iron-red oxide which contributes to the coolness of the colour. Holbein creates the ledge front by blending thin strokes of light and darker paint to create a softer edge. A thin dark red line defines the transition from stone to silk in the deepest shadows. The same deep plum red, is imperceptibly blended for the sinuous cast shadow on the stone beneath his sleeve.

The inscription

The ‘carved’ inscription has been marked out with extremely fine lines scored lightly into the deep plum paint of the ledge wall. Within these guidelines Holbein has painted his inscription freehand in two simple colours pulling one over the other for the mid-tones. It is painted with the assuredness and skill of a calligrapher. The loaded brush occasionally leaves a rounded deposit of paint as it is lifted from the paint surface. The contrast of the freehand application with the precision of design is remarkable.

Holbein has created a remarkably life-like portrait. The complete illusion of flesh and fabric, light and shadow captures the young Derich Born so convincingly that as he half turns and returns our gaze we almost believe we hear him speak.