Holbein in the Royal Collection

A closer look at Hans Holbein's works.

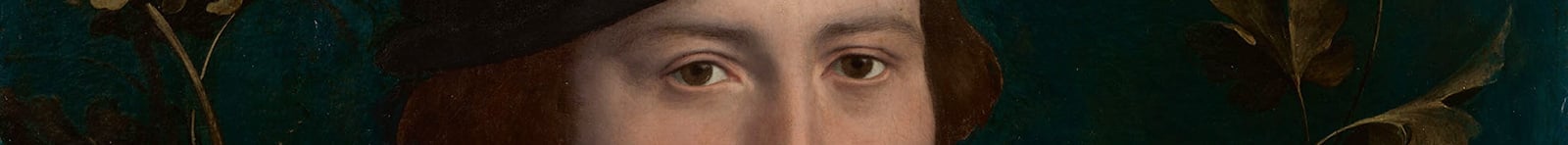

Mary Shelton

Discover Holbein's drawing of a Tudor poet.

By Kate Heard, Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings

Reading time: 3 minutes

Hans Holbein’s portrait of Mary Shelton, later Lady Heveningham, is one of the most highly worked of his drawings. He has used a range of materials to record not only the sitter’s face, but also the delicate details of her dress. No finished painting is known and this is the only portrait of Mary Shelton to survive.

Who was Mary Shelton?

Mary Shelton, born between 1510 and 1515, was a cousin of Anne Boleyn, and a friend of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. She was part of the wealthy and influential East Anglian circle who were prominent at court, and who provided Holbein with many of his sitters.

Along with Howard’s sister, Mary Fitzroy, and Lady Margaret Douglas (Henry VIII’s niece), Shelton was one of the compilers of the ‘Devonshire Manuscript’. Now in the British Library, this manuscript brings together poetry by Thomas Wyatt, Henry Howard, and others, alongside compositions by Shelton and her fellow compilers, who also inscribed comments in the margins of the verse.

Holbein’s drawing techniques

Holbein has used a rich pink paper as the base of his drawing. On top of this he has sketched the outlines of Shelton’s face and features in black chalk. In some places, such as her proper left shoulder and her chin, it is possible to see him refining his image with repeated lines. He then worked up details in different coloured chalks.

A bright yellow records the pendant and brooch she wears and the yellow fabric of her hood. Holbein also used yellow as an under layer for the fabric band at her forehead. The detail of each of the patches of yellow is picked out in red chalk, which shows the crossed pattern on her headdress, the detail of her pendant and the filigree decoration of her brooch.

Holbein used red chalk to catch the detail of her eyes and mouth, and as another layer in the band at her forehead. Brown chalk finishes this band and is also used with black chalk to give depth to the socket of Shelton’s eye. Holbein has used rough strokes of black chalk, as he often did to record the black velvet of her sleeves and bodice. Faint, wavering lines of black chalk may depict a watered silk on Shelton’s shoulders.

Holbein has also worked on the drawing with a brush, which he used to apply a white highlight to the band of her bodice (and the flowers that decorate the neckline), the shine of the pearl hanging from the pendant, the white trimming on her headdress, and the whites of her eyes. Black paint or ink is applied much more fully to give a deep black to the bodice and the velvet lappets of Shelton’s headdress, as well as to delineate the threads of her necklaces. Holbein has shown the beads she wears with little dabs of black; as he often did, he has not filled in the whole pattern, but simply recorded a section to remind himself.

He used very delicate brushwork to delineate Shelton’s eyebrows and the lashes on her upper eyelids, as well as in touches to give a convex appearance to her eyes. Her irises are very gently coloured with blue watercolour, which is not found anywhere else on the drawing. Finally, Holbein has used pen and a brown ink to draw little lines at the base and tip of Shelton’s nose.

Why was the drawing made?

Holbein’s drawing was made as a preparatory study for a painted portrait. Although we have no record of Mary Shelton’s sitting to Holbein, it must have been long enough to enable Holbein to look closely and record the figure in front of him in great detail.

The purpose of the portrait is not known, but it may have been made at the time of Shelton’s engagement to Thomas Clere in the 1540s. Clere would die in 1545, before the couple could marry, and Shelton later married Sir Anthony Heveningham. Her married name was inscribed on the drawing in the 18th century. Shelton, who died in 1571, is buried in Heveningham Church in Suffolk, England.