At Home in the Highlands

Exhibition curator Carly Collier looks at the royal couple's heartfelt fondness for the Highland way of life, both romanticised and real

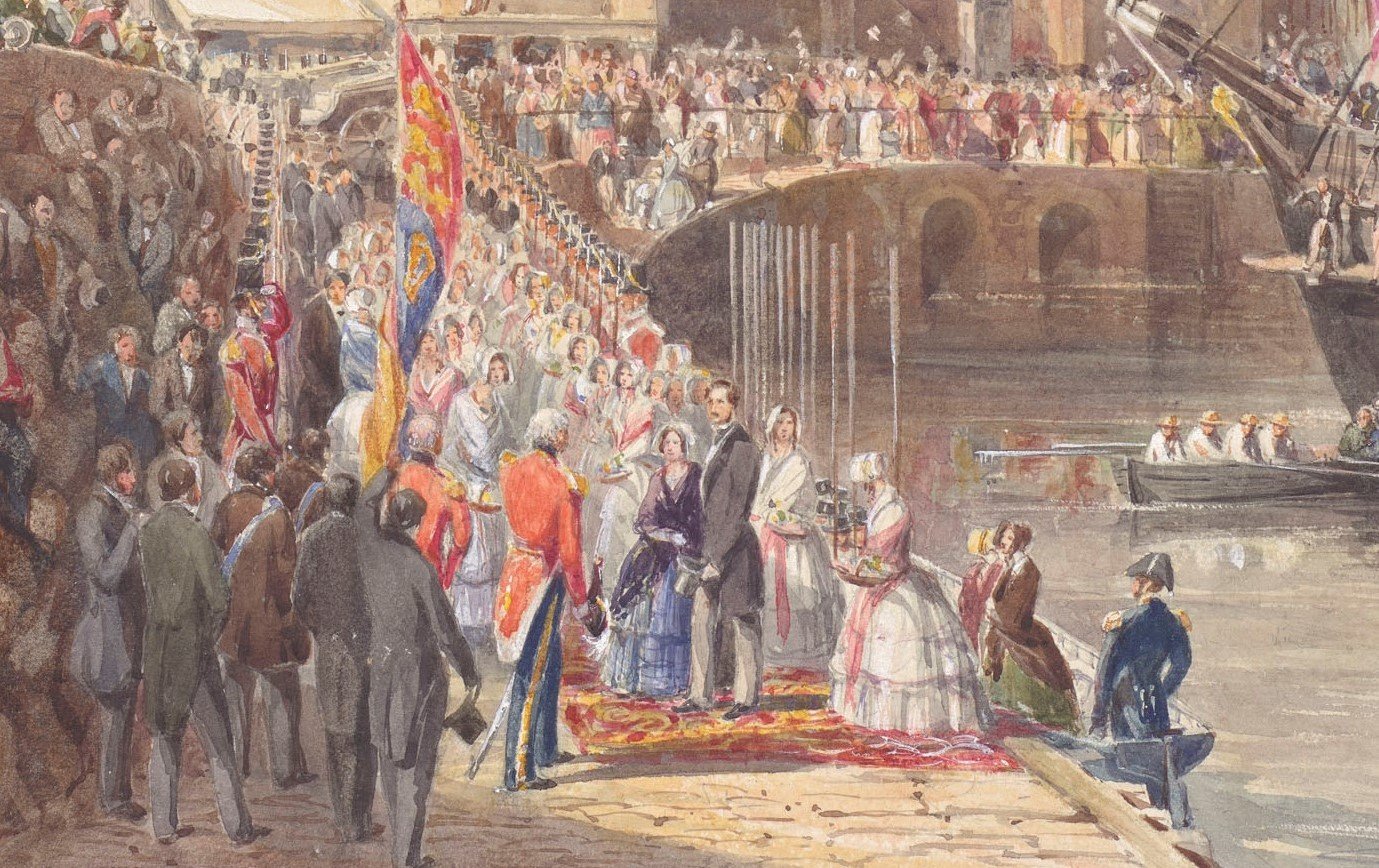

‘One cheer more!’ wrote William Wyld on the bottom-left corner of this watercolour which he painted for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1852. Wyld captured the joyful celebrations at the completion of a cairn-building ceremony to mark the royal acquisition of the Balmoral estate in the Scottish Highlands, an occasion which Victoria recorded in detail in her diary. The queen’s account and Wyld’s watercolour together illustrate Victoria and Albert’s deep, sincere love for Scotland and their enthusiastic adoption of what they saw as Scottish culture and customs.

Victoria and her young daughters appear to be wearing plaid shawls and tartan skirts, and the young princes are in kilts. The early nineteenth-century vogue for tartan – boosted by George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822 – was taken up by the English upper classes, including the royal family; as we can see here, the queen herself was painted as a baby in 1819 wearing a ‘Scotch bonnet’, and she was keen to dress her own children in tartan fabrics.

The queen and prince later designed their own tartans that were used in abundance for clothing for themselves and their retainers – Prince Albert’s gillie John Mackenzie wears a kilt made of Balmoral tartan here – as well as for furnishing their new Scottish home.

Wyld’s watercolour also features a piper, and servants handing around whisky. During Victoria and Albert’s first trip to Scotland in 1842, when they visited Edinburgh and toured the Highlands, the entertainments they enjoyed courtesy of their various hosts introduced them to Scottish customs and traditions which the couple then embraced in their own daily lives. William Ross, seen in the hand-coloured photograph here, was Piper to the Queen, the second person to hold the position created by Victoria after she and Albert became, in her words, ‘quite fond of the bagpipes’ after hearing them during their first visit.

Prior to their first visit in 1842, the royal couple’s view of Scotland was shaped by literature and art. Both Victoria and Albert had long been voracious readers of the poetry and novels of Sir Walter Scott. Scott’s romanticised version of Scottish history was matched visually by Edwin Landseer’s evocations of picturesque, untamed Scottish nature and his idealised depictions of the country’s inhabitants as living a noble and ‘authentic’ life untouched by the modern world. Landseer enjoyed a steady stream of royal patronage and indeed collaborated with the queen in developing subject pictures such as the pair shown (RCINs 401515 and 401516), in which the figures are representative types illustrating what Victoria and Albert – and many others – considered characteristic elements of Scotland’s national identity, epitomised by the Highlands and the Highlanders.

Though it wasn’t rooted in reality, Victoria and Albert’s love for Scotland was genuine and ran deep. The queen found her first return to Balmoral after her husband’s untimely death shattering, writing in her diary: ‘What a heartrending return … everything brought all back before my eyes, all the years of happiness, now gone forever!’ She found solace in rereading her diary, and particularly those entries recording the time she and Albert spent in their ‘dear Highland home’.

In the late 1860s Victoria made the unprecedented decision to publish a version of her private Scottish diaries, as ‘Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands’. As the editor’s introduction stated, this made ‘these extracts [concerning] some of the happiest hours of [Her Majesty’s] life’ accessible to all her subjects. This volume, illustrated with wood engravings reproducing photographs commissioned by the queen, was extremely popular, selling out in three months, and was translated into several different languages. Victoria wrote to her eldest daughter with some pride that ‘My book, every one says, has had such an extraordinary effect on the people’.