'Dear dear Great Expeditions'

Exhibition curator Carly Collier uncovers the royal couple's secret Highland wanderlust

Arriving home at Balmoral Castle just after 8pm on an autumnal October evening in 1861, Queen Victoria wrote a detailed account in her diary of the adventure she, her husband Prince Albert, their daughter Princess Alice and her fiancée Prince Louis of Hesse had just undertaken. Leaving Balmoral the previous morning, they had embarked on an expedition of over 100 miles (160km), travelling through ‘that beautiful Glen Feshie’ on their ponies. After an overnight stay at the Dalwhinnie Inn the royal group travelled south to Loch Garry and on to Blair Castle, where Victoria and Albert had spent three very happy weeks seventeen years before, during their second visit to Scotland.

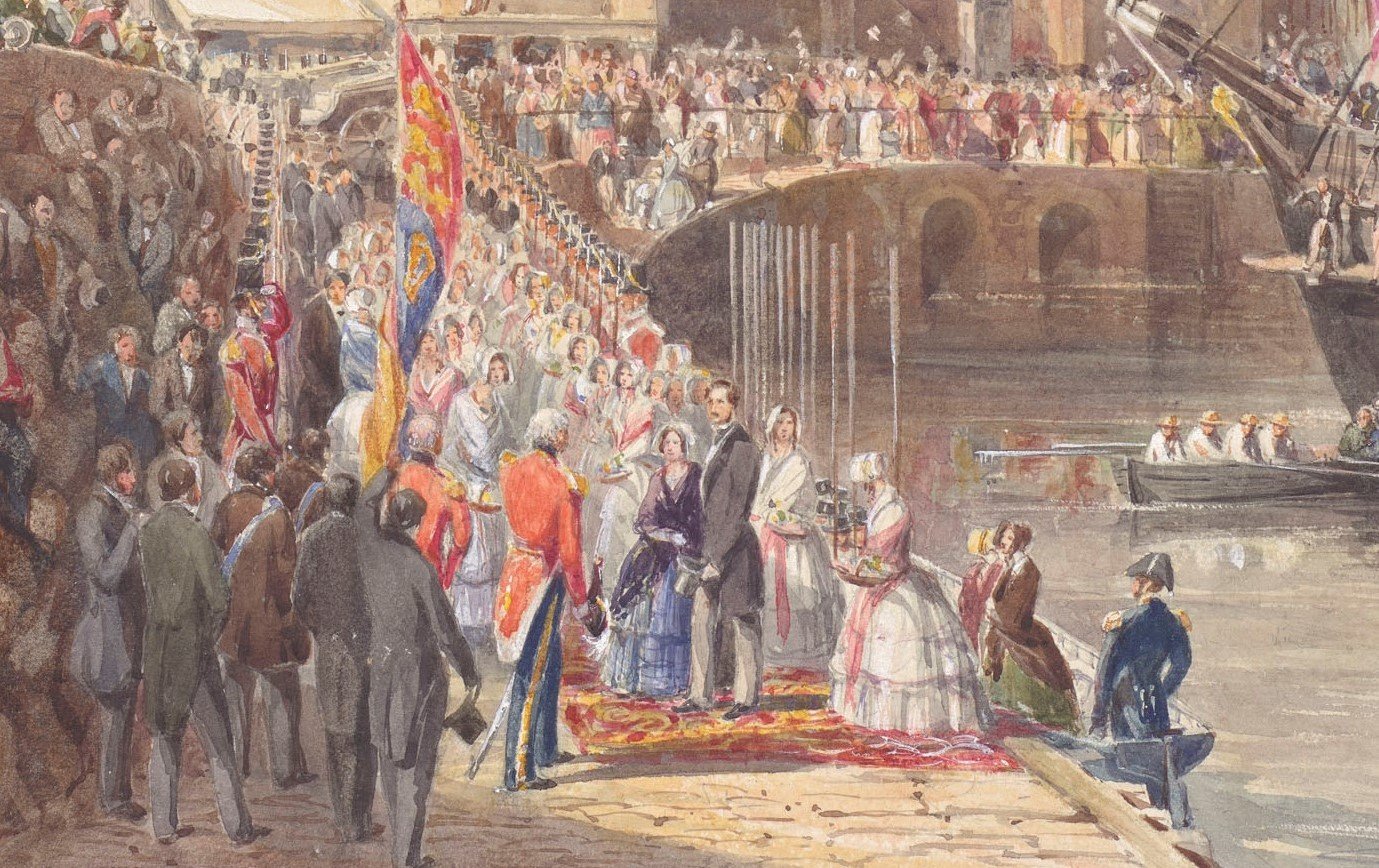

The watercolour shown depicts a moment on their journey in 1861 from Blair Castle back to Balmoral when, accompanied by the Duke of Atholl and his men, the party splashed through, in Victoria’s words, ‘the celebrated Ford of the Tarff … which is very deep & after heavy rain almost impassable … the current, from the fine high falls, is very strong … [crossing] it was quite exciting’. The queen’s record of the trip ended on a tired but happy note: ‘This was the pleasantest & most enjoyable expedition I ever took & the recollection of which will ever be most agreeable & increase my wish to make more’.

The adventure just described was the third of Victoria and Albert’s ‘Great Expeditions’. Beginning in the autumn of 1860, the couple made these excursions to scenic spots in the Highlands, some of which, as was the case at Dalwhinnie, included an overnight stay at a local inn. Victoria and Albert were, of course, used to opulence and luxury, but the queen praised the ‘nice & cheerful’ Ramsay Arms at Fetticairn, depicted here, where they stayed during the second Great Expedition on 20 September 1861. For Victoria and Albert, these experiences were a very rare taste of something approaching a ‘normal’ life. They travelled largely incognito, adopting pseudonyms such as ‘Lord and Lady Churchill’, and Victoria clearly relished the subterfuge, as her diary entries for the trips are full of her delight at hearing of ‘vague suspicions & rumours’ and the close calls when they got away without their true identities being discovered. In Fetticairn, for example, they enjoyed the freedom of a moonlit walk through the village.

A day expedition to Carn Lochan for a picnic on a beautiful day – ‘not a cloud in the bright blue sky, perfectly calm’, enthused the queen – was to form the unexpected end to these short episodes of freedom and exploration. In the third watercolour, Albert leads his wife’s pony, gesturing at the magnificent view, with Prince Louis alongside Princess Alice and her younger sister Princess Helena, allowed to accompany her parents for the first time, at the rear of the procession. Before they left Albert, perhaps with a strange prescience, ‘scribbled on a bit of paper, that we had lunched at this spot. It was put into a seltzer bottle & stuck into the ground.’

Her husband’s unforeseen death on 14 December 1861, at the age of 42, altered Queen Victoria’s life irrevocably. In her early widowhood she sought to perpetuate Albert’s memory and record special memories – the watercolours here were part of a series painted 1862-63 by Richard Principal Leitch, an artist who was close to the royal family thanks to his father’s long-standing employment as Victoria’s watercolour tutor. Looking at these visual reconstructions of some of the happiest moments the queen spent with her beloved Albert gave her comfort in her grief. As Leitch’s father William Leighton Leitch noted on his first visit to Balmoral after the prince’s death – ‘the whole place is changed … all is gone with him who was the life and soul of it all’.